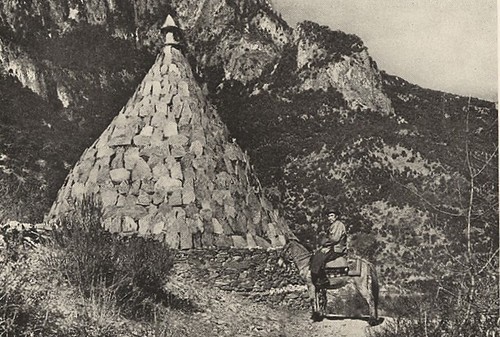

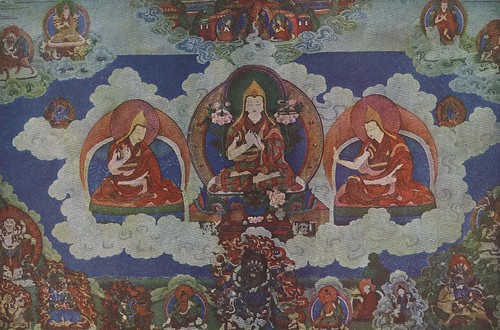

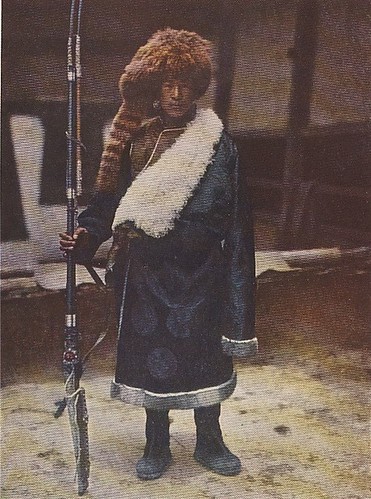

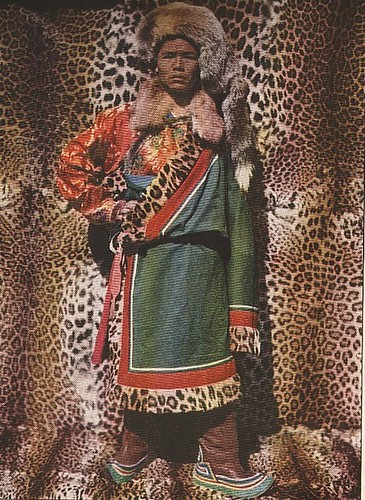

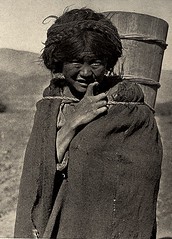

A Tibetan lama who Rock met on the trail to Muli.

To get to Muli, Rock had to cross a mountain pass about 15,000 feet high – the Gibboh Pass. As always seemed the case when crossing high passes, his caravan was hit by a blizzard near the top: he and his escort made a makeshift camp in the snow and spent an unsettled night with leopards prowling about. But they woke to a beautiful clear morning “but the cold was so intense that hot water froze on my face and hands when I attempted to make toilet”.

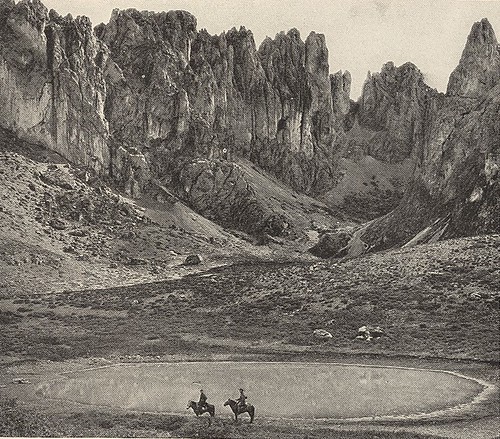

His party reached the Gibboh Pass, where he worried he would be attacked by bandits:

“We reached the pass, 15,000 feet above the sea in gorgeous sunlight. To our right was a line of crags snowcapped and glistening like diamonds. The pass is supposed to be infested with brigands, but we were not molested.”

“We reached the pass, 15,000 feet above the sea in gorgeous sunlight. To our right was a line of crags snowcapped and glistening like diamonds. The pass is supposed to be infested with brigands, but we were not molested.”

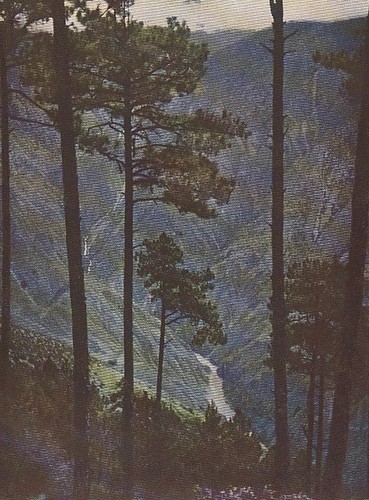

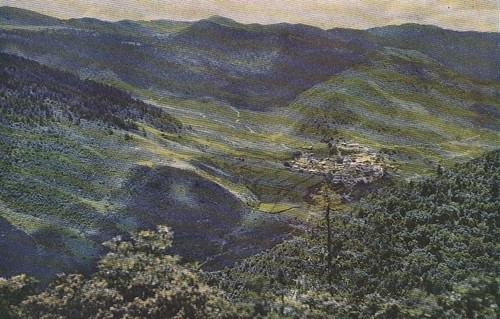

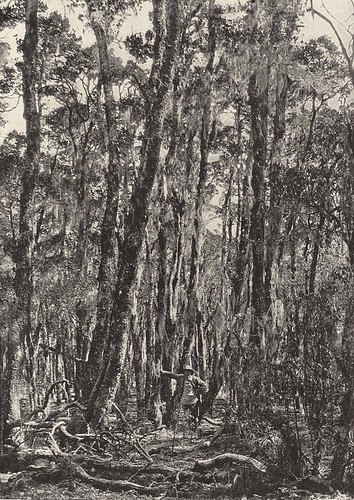

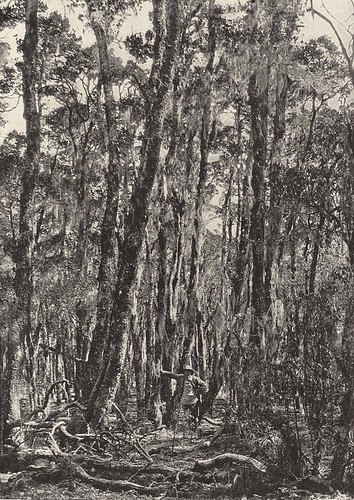

"We descended through a steep forest of spruce and fir, with rhododendron trees as underbrush; lichens and mosses covered trunks and boulders. All was hushed.”And later his soldiers suddenly pointed out the city on a hill. It must have been an even more splendid sight then as the ruins had been for me:

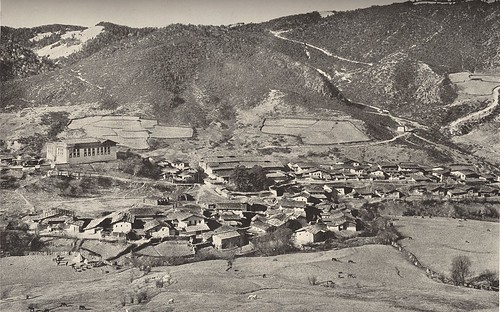

“One of my soldiers took me to an open spur and pointed north, where upon a sloping hillside lay Muli, bathed in the sunlight. I also looked upon a sea of mountains, range after range, like furrows in a field, with a deep ravive from north to south down which runs the Litang river.”Before entering Muli, Rock pitched camp nearby and sent a soldier in to the walled city to deliver his visiting card to the lama king. He wanted to make a grand entrance. While waiting, he met the first Muli people – some Pumi women who came to trade barley for his horses to eat:

“Their wealth of hair, a good deal of it false, was decorated with garlands of gilded Szechwan rupees, a coin common in this region.”

The next day he rode up to the walled city on the hill. On his arrival he was greeted by a Tibetan lama in a crimson robe who bowed deeply and made a formal speech of welcome after presenting the king of Muli’s card. The stranger, Joseph Rock was invited into the king’s domain.

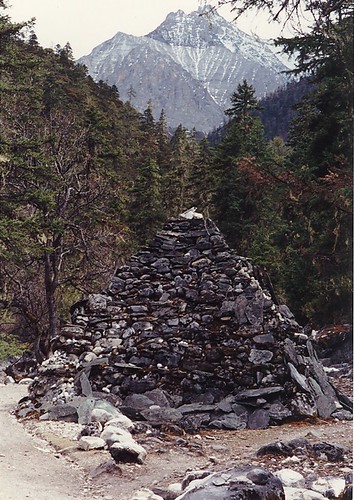

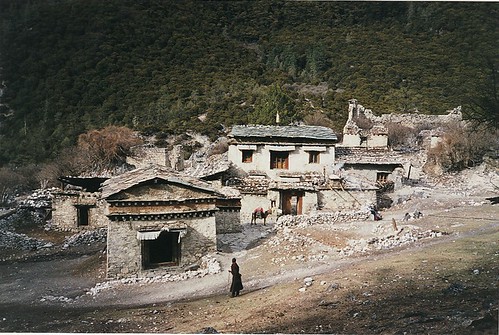

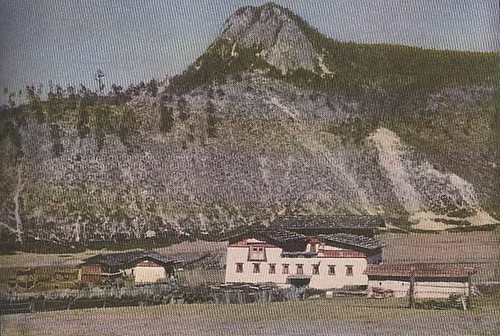

Passing pyramids of mani stones on the way, Joseph Rock made the grand entrance to Muli that he desired:

“A row of courtly priests stood in waiting and bowed at my approach. I was conducted along the wall to a new house with a terrace, outside of Muli proper, and when I was comfortably settled I was asked when I wished to see the king, who was anxious to see the stranger.”

Rock changed from his riding wear into something more suitable for meeting the regent or

Gyalpo of this tiny kingdom. He took with him his Thai boy servant, Tibetan cook and two Nashi servants, dressed in their finest, and carrying his gift to the Muli king: a gun with 250 rounds of ammunition.

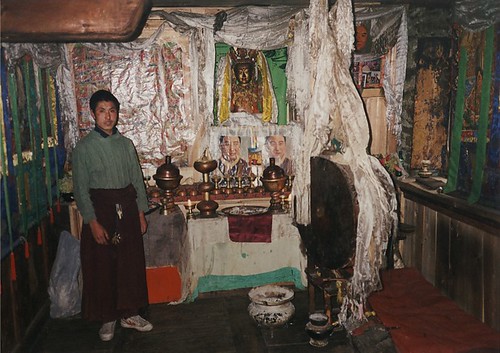

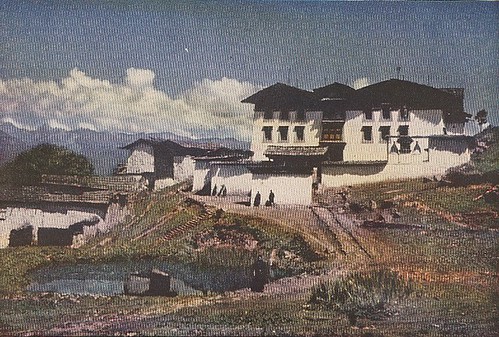

In the palace square he heard the weird sounds of trumpets, drums, gongs and conch shells emanating from within the main temple. He entered via an imposing gateway flanked by two large bundles of whips and was led inside, up a dark staircase and into an anteroom guarded by a greasy curtain “black from the marks of buttered fingers”.

From here he was taken into the brightly lit reception room to meet the king himself. Rock’s description of his first meeting sounds like the scene in Apocalypse now where Willard finally meets Colonel Kurtz:

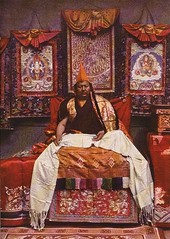

“On my approach he rose, bowed and beckoned me to a chair next to a small table loaded with Muli delicacies. He occupied a chair, facing me. I had great difficulty in distinguishing my hosts features as he sat with his back to the light coming from an open bay window, while he watched every muscle of my face.”The 36 year old king, Chote Chaba, - or “Hsiang tzu Cheng Cha Pa” in Chinese - was a heavy, rotund man with weak muscles – "as he neither exercises nor works". And yet his manner was “dignified and kind, his laugh gentle and his gestures graceful.” The king wore the traditional Tibetan lama’s red toga-like garment, which left the left arm bare. Beneath his tunic he wore a gold and silver brocaded vest, and had a rosary beads clenched in his left hand.

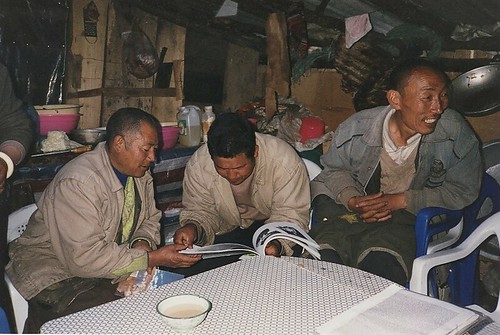

The king was accompanied by his two brothers: the younger one also a lama, the elder a “coarse individual who looks more like a coolie than a prince”. There were also several lesser lama servants in the room, cringeing with bowed heads and clasped hands, waiting deferentially for the next royal command. When dismissed, they left the room walking backwards, bowing and gesturing in acquiescence towards the king

When Rock began to speak with the king, he quickly discovered how little this all-powerful ruler knew about the outside world. The king did not know who ruled China, and asked whether he would be able to ride on horseback to Washington DC. He asked to borrow Rock’s binoculars, which he believed could see through mountains. The king also believed that thunder was made by dragons within the clouds.

And yet there were a few odd western touches to the King of Muli’s living quarters. A row of kerosene lamps had been hung up for decoration [there was no kerosene for hundreds of miles: “no matches or candles could be had here, and the black greasy necks of the lamas – including the king and Living Buddha – showed that soap was not in demand”] Some modern coat hooks hung on the pillars - “like you would expect to see in a cheap German beer garden”. And the king summoned his servants to bring a collection of old photographs depicting scenes from the White House, Windsor Castle and Norwegian fiords, for which Rock tried to explain the meaning.

Later Rock was to discover a room full of photographic equipment, all completely unused, as the Muli lamas had no idea how to operate it. It was a gift from a wealthy Chinese trader. Rock advised the king to use the glass photographic plates to glaze his windows. And at another nearby monastery he stumbled across a room full of clocks, all ticking away, and yet none of the lamas could tell the time.

Rock dined with the king of Muli that day bit found the food did not come up to the standards of the plates it was served upon. Muli delicacies served on golden plates included rancid yak cheese complete with bits of yak hair, and the usual butter tea [“like liquid salted mud”] served in exquisite porcelain cups with silver filigree. Rock was later given some of the choicest items from the king’s larder, which included a wormy ham that literally walked around by itself, propelled by “squirming maggots the size of a man’s thumb”. Rock had his servants throw it to some Muli peasants waiting outside his room, who fought over the rotten meat like tigers.

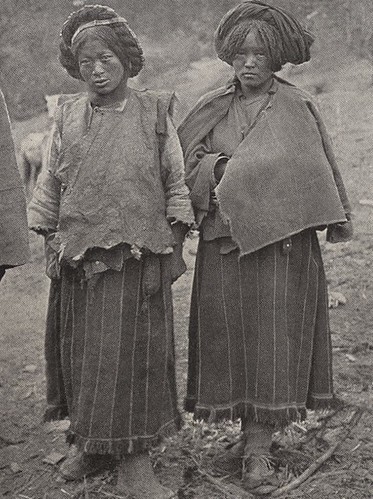

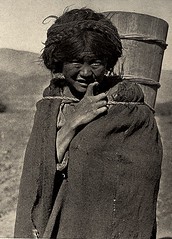

Muli beggar

Muli beggarIn return, Rock gave the lamas and king’s servants some silver coins and bars of soap.

And while he listed to the drums, gongs and the deep bass voices of some of the lamas reciting their prayers, he read the king of Muli’s card. His full title was “self existent Buddha, Min Chi Hutuktu, , possessor of the first order of the striped tiger, former leader of the Buddhist church in the office of occupation commissioner, actual investigation officer in matters relating to the affairs of the barbarous tribes; honorary major general of the army and hereditary civil governor of Muli.” Honorific: Opening of Mercy.

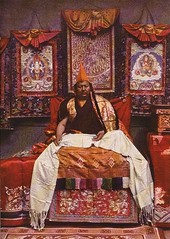

During his first stay at Muli Rock made formal photographic portraits of the king using his large and cumbersome Eastman Kodak box camera on a tripod. I think this is one reason why Rock’s pictures are so good: every photograph is well composed, an “occasion”, he was more akin to a portrait painter than a photojournalist. And later when he travelled in the company of a young American he ridiculed his “rushing around snapping at everything without a tripod”.

Rock visited the king’s residence at the top of the Muli compound, known as the Churah, where he took pictures of the king on his throne, covered with ornate blankets and with his three King Charles spaniels shooed away at the last moment. In return for taking pictures of himself and his lama officials, the king rewarded Rock with some pulu bolts of cloth and the rosary that had been wrapped around his left wrist.

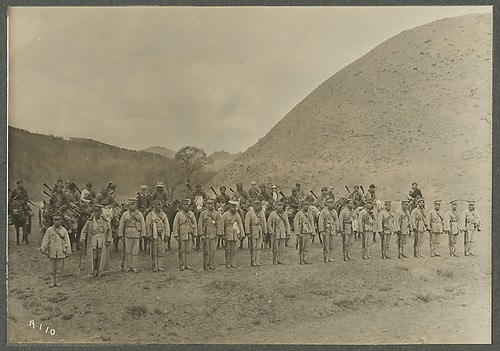

Later, Rock also photographed the king’s bodyguard in their ceremonial robes, and the Living Buddha of Muli - a boy of 18 - in his splendid robes, mounted on a specially decorated horse.

The next day Rock was invited to a special banquet of hotpot and vegetables, with a dessert of pure cream, which the king lapped up from the bowl with his tongue.

On his last evening in Muli Rock was treated to a special dusk ceremony to ward off devils. Just beneath his residence the lamas gathered in a circle around an oak brush bonfire, which they set alight and cast on images of devils which they wished to banish. Amid beating of drums, crashing of cymbals and the blowing of the bass notes on huge 12-foot long trumpets, the 40 yellow crested lamas, lead by a Ghiku – abbott – dispelled the demons were driven into the flames, and night fell on Muli.

Early the next morning, Rock again met with the king of Muli, said his farewells, because he was going out into the hills to pray. He presented Rock with a tray loaded with gifts – among which were a golden bowl, two buddha statues and a leopard skin.

He saw Rock to the gates of his palace – and his appearance caused the lowly folk of Muli to flee in terror. The officials, magistrates and lamas of this self contained town formed a line to the gate and bowed to Rock as he departed before sunrise.

As he ascended into the hills, he marvelled at the

“vast sea of ranges, pink and yellow, with black slopes indicating fir forests … the deep valleys lined on both sides with snow-capped crags.”Muli lay on the hillside below him,

“beautiful in the morning sun, an oak forest surrounding it like a sombre garland.”“A peculiar loneliness stole into my heart as I rode through the firs draped with long yellowish lichens. I thought of the kindly, primitive friends who I had just left, living secluded from the world, buried among the mountains, untouched by and ignorant of Western life.”Rock’s party ascended up to a camping ground at 12,000 feet amid a fir forest, as they prepared t recross the Gibboh pass.

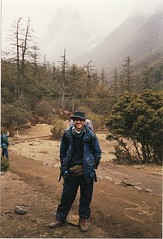

“There I let my dreams take me back once more to Muli, that weird fairyland of the mountains, where its gold and riches of the Middle Ages contrast with butter lamps and pine torches.” Joseph Rock near the Giboh Pass, 1924

Joseph Rock near the Giboh Pass, 1924 My guide near the Giboh Pass, 2003.

My guide near the Giboh Pass, 2003..