[Click here to go forward to Chapter 6]

Joseph Rock starts off his October 1930 National Geographic article "Glories of the Minya Konka" with a typical flourish of exaggeration:

Joseph Rock starts off his October 1930 National Geographic article "Glories of the Minya Konka" with a typical flourish of exaggeration:"Strange as it may seem, hoary old China still holds within its borders vast mountain systems wholly unknown not only to the western world, but to the Chinese themselves."What a load of guff! Far from being 'wholly unkown', by the early 20th century, the 25,000 foot high mountain peak of Gongga Shan in western Sichuan - known then as Minya Konka - was already well known to the Chinese, and had even been visited by several Europeans - including Rock's fellow botanist Ernest Wilson, in 1908.

In his article, Rock describes an epic journey that he made to a remote mountain of sublime beauty. It was an article that could well have inspired the whole Shangri-La legend as developed by James Hilton in his novel Lost Horizons. The scenarios are similar, and Hilton's novel came out in the mid 1930s - just a few years after Rock published his articles in National Geographic. Rock writes of his journey to a tiny monastery located in an isolated valley, where a temple is perched above a glacier at the foot of a huge mountain. According to Rock, this monastery was cut off from the rest of the world by snow-bound passes for six months of the year, and its views of the mountain were so spectacular that a visit was deemed by Buddhists to be the equivalent to ten years of meditation!

According to Rock, he was inspired to make the trip to Minya Konka after glimpsing a view of this 'mysterious' peak in 1928, while he was exploring the Konkaling mountains near Muli. Viewing the peak from the south west, at a distance of about a hundred miles away, he claims to have been smitten by this 'unknown' peak.

"I decided then and there to spend the following year exploring Minya Konka," he writes.

And thus it was that in the spring of 1929 Rock mounted an expedition to Minya Konka from his base at Ngluluko near Lijiang.

Unlike his 'quick dash to Muli', this was to be a major undertaking, and Rock planned to a journey of several months, to be accompanied by an entourage of 20 Naxi porters, bodyguards and helpers and 46 mules carrying supplies. To reach Minya Konka, Rock's caravan had to travel north-east, via Muli, on a journey that would take several weeks over epic terrain. It would involve the crossing of the vast canyons of the Yangtze and Yalong rivers, and crossing several high mountain barriers to reach the domain of the 'Minya' Tibetans.

In contrast to the 'uncouth, impudent' and aggressive Tibetan robber tribes that he had previously encountered around Muli, Joseph Rock found that the Tibetans he met in the Minya region were 'a gentle race'. The Minya Tibetans were a settled, agrarian people who lived in fear of the marauding Xiangcheng Tibetan bandits. They built watchtowers and fortress-like solid stone houses to resist the attacks.

While visiting Minya Konka, Rock based himself in the Yulonghsi valley, near the town of Tachienlu (now known as Kangding). However, despite its proximity to the Minya Konka peaks, the mountain is not visible from Yulonghsi. Along with the other peaks in the range, Minya Konka was hidden away behind a high ridge that had to be crossed at the Tsemi pass to gain access to the mountains.

"Anyone unfamiliar with the geography of the country could, even with the latest maps in hand, pass up this valley without suspecting the existence of the Minya Konka range, crowned by one of the loftiest peaks of western China... And yet, these majestic snow peaks lie just beyond the high eastern valley slopes of Yulonghsi."When I started planning my own trip to Gongga Shan I found that, unlike my trip to Muli, there were a few modern maps available for the Minya Konka region. A quick perusal suggested that there were two possible ways of getting to the mountain - either from the north, directly from Kangding, via a valley that starts at a village called Lao Yulin, or from the west, via a settlement called Liuba. This latter approach would entail travelling in huge counter-clockwise arc to reach Yulonghsi - a two-day road trip westwards from Kangding, crossing a high pass called Zheduo La, and then turning south along a minor road for about fifty miles until reaching a turnoff for Liuba. None of the modern maps actually showed a settlement called Yulonghsi, but there was a valley marked on the map in roughly the same the place as where Rock said it should be.

And so September 1995 found me landing back in Hong Kong, with a plan to try re-trace Joseph Rocks' journey in reverse, starting from Kangding and trekking south via Minya Konka, all the way to Lijiang, via Muli. My idea of repeating this epic journey was a wildly overambitious plan that in retrospect had no chance of succeeding. Rock had spent months making the journey to Minya Konka and had the support of a huge team of porters and mules for transport. I naively believed that I could do the same trip by myself in a couple of weeks as a backpacker, taking only a tent, sleeping bag and a few days worth of food.

I didn't linger for long in what was then still the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong. Despite it being autumn, the city was still uncomfortably hot, crowded and noisy. To escape the heat, I dropped my passport off for a China visa at the China Travel Service office in Tsim Sha Tsui, and took off to what I thought would be the relative quiet and cool of the grassy hills of Lantau Island, where I camped out for a night on Sunset Peak. Although I was up at an altitude of almost 1000 metres, it was still hot up in the hills, and thanks to Hong Kong's smog-laden air, I saw neither sunset nor sunrise, just a soupy gloom.

I didn't linger for long in what was then still the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong. Despite it being autumn, the city was still uncomfortably hot, crowded and noisy. To escape the heat, I dropped my passport off for a China visa at the China Travel Service office in Tsim Sha Tsui, and took off to what I thought would be the relative quiet and cool of the grassy hills of Lantau Island, where I camped out for a night on Sunset Peak. Although I was up at an altitude of almost 1000 metres, it was still hot up in the hills, and thanks to Hong Kong's smog-laden air, I saw neither sunset nor sunrise, just a soupy gloom. Down below, in the murk, Hong Kong's new airport was being constructed offshore at Chep Lap Kok. On the bus back to the Mui Wo (Silvermine Bay) ferry terminal I found myself sitting behind a couple of young British labourers, who were working on the new airport construction site. They were bragging loudly about getting pissed and shagging, and almost every sentence they uttered had the word 'fuck' in it. Sat on a bus full of otherwise impassive and demur Chinese passengers, I cringed at the behaviour of my compatriots and felt embarrassed to be British. The last cries of empire.

After a night in one of the eight-bunk rooms at the STB Hostel in Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon, I picked up my China visa from the remarkably efficient CTS and was on my way. I flew into Chengdu, where I stayed at the Traffic Hotel located by the river, right next door to the long distance bus station.

It was an arduous two day road journey to Kangding, the old bus grinding up from the plains of Sichuan over the old road across the Erlang Shan pass. We had to overnight in a filthy hotel in the grim lowland town of Ya'an at the foot of the hills.

On the second day we really started to gain altitude as we followed the winding road up to the 4000 metre Erlang Shan pass. This ridge was the traditional physical barrier between China and Tibet. The road went up through precipitous gorges, carrying cascading torrents of rivers past hideously ugly and primitive 1960s-era cement factories and hydro-electric dams that had been plonked unsympathetically into this epic and wild landscape.

The bus groaned and shuddered up the switchback road, past sections where whole chunks of the hillside had fallen away, causing the bus to detour around massive slabs of rock and mud that lay in the middle of the road. The stop-start progress could be excruciatingly slow, and sometimes our bus was halted behind a long line of other trucks and buses as long convoys of green PLA trucks were given right of way to pass us.

The road, ostensibly one of the main highways linking with Sichuan and Tibet, became something resembling a switchback dirt track as it reached its highest point in the mountains. We finally lurched over the summit of the Erlang Shan road in grey mist, and began an equally tortuous descent towards the Dadu river and the famous town of Luding. In the late 1990s the Chinese bored a 4km long tunnel through Erlang Shan, cutting out the worst parts of the summit road, and also cutting the travel time between Chengdu and Sichuan down to a single day. But in 1995 I was still doing it the hard way.

Our bus paused briefly in Luding, enough for me to catch a glimpse of the famous old iron-chain bridge. According to revolutionary legend, this 18th century structure had been supposedly captured from the Kuomintang in a daring near-suicidal attack by the Communists during the Long March in 1935. Luding was a vital river crossing for the Mao's Red Army forces because it was their only way of escaping northwards away from the superior armies of Chiang Kai Shek's KMT. In the Communist propaganda telling of the story, Luding bridge was captured by a daring squad of Red volunteers who crawled across the bare bridge chains above the river into a hail of bullets coming from the KMT soldiers holding the other side.

More recently, historians have discovered that the Luding bridge crossing may have been much less dramatic. Rather than being heavily fought over, witnesses say the bridge was actually defended by only a small group of local men with muskets who were in the pay of a local warlord called Liu Wenhui. Liu had been paid off by the Communist envoys, and had agreed to put up only token resistance to the Red Army.

From Luding, the road to Tibet resumes its upwards trajectory and runs up an increasingly narrow canyon that also contains a narrow but turbulent river whose waters surge over huge boulders. At one point there is a Tibetan stupa by the river - the first sign of Tibetan cultural influence. And then, in the late afternoon I finally arrived at my jumping off point of Kangding.

In his writings, Rock has very little to say about the town that was then known as Tachienlu (the sincised version of the town's Tibetan name, Datsendo). He barely mentions it in the text of his article about visiting Minya Konka, except to say that he sojourned there for nearly two weeks, overcoming his disdain of western 'holy rollers' to stay at the China Inland Mission. In Kangding, Rock was able to replenish supplies, develop his colour negatives and give his mules a rest. One of the photographs accompanying his article shows the town clustered along the banks of the river, looking little different in layout from the modern Kangding - although all the buildings appear to be single story traditional Chinese houses with curving tiled roofs. Standing out from them is the imposing structure of a Christian church, built in the European style with large arched windows and an ornate Gothic façade complete with spires and towers. It is certainly as Rock outs it: "one of the most imposing Christian churches in this part of the world".

In his writings, Rock has very little to say about the town that was then known as Tachienlu (the sincised version of the town's Tibetan name, Datsendo). He barely mentions it in the text of his article about visiting Minya Konka, except to say that he sojourned there for nearly two weeks, overcoming his disdain of western 'holy rollers' to stay at the China Inland Mission. In Kangding, Rock was able to replenish supplies, develop his colour negatives and give his mules a rest. One of the photographs accompanying his article shows the town clustered along the banks of the river, looking little different in layout from the modern Kangding - although all the buildings appear to be single story traditional Chinese houses with curving tiled roofs. Standing out from them is the imposing structure of a Christian church, built in the European style with large arched windows and an ornate Gothic façade complete with spires and towers. It is certainly as Rock outs it: "one of the most imposing Christian churches in this part of the world".

The church was one of several built in the region by French missionaries such as Père Jean-Baptiste Ouvrard in the late 19th century. This particular one was the Church of the Sacred Heart, completed in 1912 by Ouvrard, who we shall meet again later in relation to his activities in the Salween and Mekong valleys further west.

The mission stations were usually built one day's riding distance from each other, and missionaries penetrated as far as remote Tibetan towns such as Batang, hoping to convert the heathen Buddhists to Christianity. At the time of Rock's visit there were several missionaries in Tatsienlu, as well a handful of western traders. Despite running schools, hospitals and orphanages, the missionaries failed to win over many Tibetan converts. However, there is still a Catholic church in Kangding, a gaudy rebuilt edifice by the riverbank, said to be host to 200 practising Christians. I visited the church on one of my later trips through Kangding, and was given a tour of the place by the friendly caretaker. Unlike the exterior, the interior was a restrained and serene place, where I found wooden pews stacked with hymnals decorated in the pre-Vatican II style.

At 2600 metres in altitude, Kangding reminded me a little of Arthurs Pass in New Zealand. A small town squeezed into a narrow, steep-sided valley between two sets of high mountains, Kangding is still the cultural border between Han China and Tibet. While most of the town's population is Han Chinese, in 1995 there were still enough Tibetans in town to make it feel like I had finally arrived at the gateway to Tibet. Founded on the confluence of two rivers, Kangding has for centuries been an important trading centre, where tea and tobacco were brought up from China, and where Tibetan herdsmen brought their leather, furs and woolen wares down from the highlands to sell.

Photo: Neil Gibson

Photo: Neil GibsonIn 1908 the American consul described 'Tatsienlu' as a small town of 9000 people, mostly Tibetans.

"A large trade is done here in rhubarb and musk, the latter taken from the small hornless deer plentiful in this part of China. Of the exports of this district musk is the most valuable ... Next in importance of exports is wool. This trade of late has diminished, owing to the disturbances on the border. The coarse sack-like wool cloth 'mu-tsz' is worn by all Chinese coolies, while a fine grade dyed red called 'pulu' is the clothing of the higher class of the Tibetans. The lower classes, such as yak and pony drivers, wear entirely undressed sheepskins. About 45,000 pounds of wool is received annually in Tatsienlu."

Gold was also traded in Tatsienlu, but as the consul noted:

"The Tibetan confines mining to washing the alluvial sand in the river beds. He is averse to outsiders mining in his country, his antipathy to them being very great. The Tibetan wishes to be let alone and strongly resents foreign intrusion."

Kangding was also a key link in the 'tea horse road'. Tea was a much sought-after commodity by the Tibetans, and bricks of tea were brought up to Kangding by coolies from the tea plantations of Sichuan:

"The tea packages are made up in rolls about 3 feet long. Each carrier will take on his back from five to thirteen, according to his age and strength," the US consul noted.

Kangding is now part of the Ganze district of Sichuan, but at the time of Rock's visit it was at the outer edge of the Chinese world. Tibet itself was effectively an independent state, and its borderlands were a turbulent area of power struggles between Chinese-backed warlords and the then considerable power of the lamas, backed by Lhasa.

In the 1930s, 'Tatsienlu' was part of a now defunct province known as Sikang, which essentially comprised the Tibetan borderlands adjacent to Sichuan. These had come under Chinese jurisdiction several decades before the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1951.

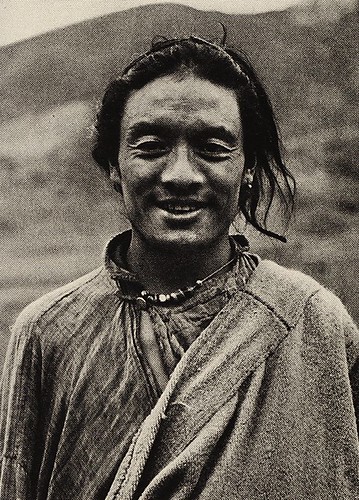

Kangding was - and still is - one of the most important centres for Kham Tibetans. Of the many different tribes of Tibet, the Khampas are renowned for their aggressive cowboy-like spirit. Elsewhere in Tibet they have long been feared as violent bandits, or admired as tough warriors. And when I arrived in Kangding in 1995 you could still see Khampa men swaggering through town in their Tibetan chubas, exposing one shoulder to the cold mountain air. They wore their hair long and shaggy, and many had the traditional threads of red wool tied into their hair. All the Khampa men carried traditional Tibetan daggers in ornate silver sheaths - some wore them ostentatiously on their belt, while others - even those wearing western style suits, would occasionally give an unintended flash of their knives while bending over or when opening their jackets.

In 1995 I stayed at the only place in Kangding that was open to foreigners - the gloomy and bureaucratic Kangding Hotel, located at the top of the town, right next door to the Anjue Si monastery.

I spent a day pottering about the old town, poking my nose into the many little shops and restaurants. Walking by the river, I bumped into a friendly group of monks who had just returned from living in India. They were escorted by a young English-speaking woman from Sikkim, who invited me to join their group in a trip out to the hot springs at Er Dao Qiao.

Later in the day I visited the other big monastery, Nanwu Si, on the outer edge of town. In Rock's article he calls it the 'Thunderbolt Monastery', and it appears to be set in almost open countryside. In 1995, however, the monastery was hemmed in by four-storey apartment blocks, an army barracks and a messy truck repair workshop. The monks there were friendly, though, and reacted eagerly when they saw my pictures from the 1920s - pointing at the old images of the Konka Gompa and reassuring me that it was still there, and still worth a visit.

Trek Day 1: Kangding to Djesi La

My plan was to take a bus around the western side of Gongga Shan to the turnoff for Liuba, and walk up the Yulonghsi valley that runs parallel to the Minya Konka range. But I chickened out. Stood in the cold, dark and clamorous Kangding bus station at 6.30am among a horde of jostling Tibetans and Chinese piling on the rickety bus, I lost my nerve, and decided I simply could not face another day on another bus.

(Photo:Neil Gibson)

(Photo:Neil Gibson)Instead, I trudged miserably back up through dark and deserted streets of Kangding and decided that I would at least take a walk out to the west of town to see if I could find a way to approach the mountains from the east, via Lao Yulin. As I walked and it got light, Chinese kids were setting off for school, and they laughed at me, the foreigner, and taunted me with the usual cries of "Allo! Laowai!"

It was an uphill hike out of town along the main Sichuan-Tibet highway, until I found a side track that took me up the left hand side of a small river, along a valley dotted with a few decrepit buildings and shacks. Soon I was walking on my own and got my first glimpse ahead of me of a row of rounded snow peaks, to the southwest. At last, I was in mountain country!

After an hour or so I arrived in what I presumed was Lao Yulin village. It was a depressing sight: just a concrete shell of an abandoned woollen mill, some slum apartment blocks and a few stone shacks dotted about the riverside. There was also a grim brick bath-house built around some hot springs, and the woman attendant there added to my pessimistic mood when she informed me that it was impossible to get through to Gongga Shan because of the heavy snows at this time of year.

I nevertheless continued up a rough gravel road towards a higher village of stone Tibetan houses. Struggling under the weight of my backpack and gasping because of the altitude, it quickly became apparent to me that despite my ambitious hopes, there was no way I could trek by myself to Gongga Shan.

I stopped for a breather outside one stone house that had some mules grazing in the backyard. When a Tibetan man appeared, I asked him out of interest how long it would take to get to Gongga Shan on foot. He sneered at the idea.

I stopped for a breather outside one stone house that had some mules grazing in the backyard. When a Tibetan man appeared, I asked him out of interest how long it would take to get to Gongga Shan on foot. He sneered at the idea."On foot? Ha! Nobody goes all the way on foot. It's too far. You have to take a horse!"

So I asked him how much it would cost to hire horses to go to the mountain.

The answer that came straight back was 15 yuan a day for a horse for me, and 20 yuan a day for his services as a guide, plus 20 yuan for his horse. Did I want to go?

I was taken aback by his sudden offer and asked how long it would take to get to the mountain. And was it possible to get to the monastery?

Yes, he knew the Konka Gompa monastery - he called it 'Gongga Si'.

"Three days to get to the monastery from here, so six days there and back. Including a horse for me it would be around 400 yuan in total," he said. "Well, going or not?"

I liked the look of his horses and so I agreed on the spot for him to act as my guide. The man's name was Gerler, he was short and stocky, with wild hair, deeply tanned brown skin and stained yellow teeth. He invited me into his house to wait in his spartan living room while he got the horses ready. There was little in the room - just some solid wooden chairs and tables, and a few family portraits of his Tibetan relatives, stuck in a picture frame. Some of the older black and white photos looked like they were from the sixties or seventies, and showed what I presumed was Gerler's family dressed in Mao suits and caps, posing in a group with serious expressions.

A small crowd of kids and other youths gathered to watch as Gerler selected two ponies and started to hammer horse shoes onto their hooves. He then brought out two Tibetan saddles, which were wooden A-frames covered with thick rugs. My horse riding experience was limited to donkey rides along the beach at Bridlington and Scarborough. What am I letting myself in for? I wondered.

Before I had time to ponder too much on this, Gerler was strapping my backpack onto one of the saddles and urging me to get on the horse. "Zou ba!" ("Let's go"). He held out the stirrup and I inserted my boot and swung myself gingerly into the saddle. What an odd feeling, to have what seemed to be a huge, lurching and unpredictable living and breathing beast as your mode of transport. I grasped the reins nervously, and Gerler told me that if I wanted to stop the horse I should pull the reins in, thus pulling the horses head back and upwards. And if I wanted to make the horse go? He lifted up the end of the rope, which had a red tip, and flicked the horse's rump with it. "Cho!"

Before I had time to ponder too much on this, Gerler was strapping my backpack onto one of the saddles and urging me to get on the horse. "Zou ba!" ("Let's go"). He held out the stirrup and I inserted my boot and swung myself gingerly into the saddle. What an odd feeling, to have what seemed to be a huge, lurching and unpredictable living and breathing beast as your mode of transport. I grasped the reins nervously, and Gerler told me that if I wanted to stop the horse I should pull the reins in, thus pulling the horses head back and upwards. And if I wanted to make the horse go? He lifted up the end of the rope, which had a red tip, and flicked the horse's rump with it. "Cho!"And the horse seemed to shoot out from under me, lurching forwards along the dirt track, dragging me along, bobbing and tilting and trying to keep my balance on top. It was not a pleasant experience, and I didn't feel like a natural in the saddle.

Gerler climbed in the saddle and followed after me, soon catching up and passing me as he spurred his small horse to a canter by digging in his heels and waving the red tipped rope. My horse started to speed up as well and I groaned in fear as I held on for grim life.

"Don't let the horse see the red rope," shouted Gerler as we cantered crazily up the rocky trail. "When he see the rope he will try to gallop."

I gathered up the rope in my hands and concealed the end in my clenched fist. Eventually our horses settled into a steady walking pace, but I still felt that my tenure in the saddle was extremely precarious.

As we headed up the lane, past the houses of Gerler's neighbours, he called out a greeting of "Gadoh!" to the people he saw in the yards, and told them where he was going.

"Taking the foreigner up to the Gongga Si - back in a few days!"

One guy asked how much he was getting paid.

"Four hundred!" said Gerler proudly.

The reply was a rising and falling "Ooh-uh-oh" that I was to hear used many times by the local Tibetans, and which seemed to be a way of saying "Yes, I hear you."

The first section of the dirt track was quite good, and was in fact part of a motorable road being constructed to go over to the Hailuoguo glacier on the eastern face of Gongga Shan. After some ascent, however, we left the village behind us and forked off onto a smaller mud track to the left and over a bridge. We were getting out into the open hills.

It was spitting rain as we continued up a gloomy and barren valley. The treeless landscape resembled the moorlands of Yorkshire, but on a much grander scale. Occasionally we passed some black yak hair tents belonging to yak herders, but there were no people about. As we plodded on for hour after hour I became a little more confident in the saddle but also a lot more uncomfortable - the stirrups were far too short for my long legs, which were bent back on themselves, making my knees and calves increasngly cramped and painful after a while.

With the low cloud, there was little else to see except the walls of the valley and the occasional black dots of yaks or dzo (a yak-bull cross) grazing high on the hillsides. Gerler led the way, wearing a cowboy hat and with pumps on his feet. He would turn around in the saddle and give me a smile from time to time, asking if I was alright. I wasn't. My horse seemed very skittish and unco-operative. It would stop from time to time to munch at grass or take a drink of water, and when I tried to spur the beast on again it would bolt off at speed at the first sign of the red rope, with me tugging grimly on the reins until Gerler caught up to rein in the recalcitrant beast. And so it was that I spent much of the afternoon of the first day.

By the late afternoon I was worrying about where we were to stay for the night. The bare hills had no sign of houses, and I wondered whether I would be pitching my tent somewhere out here in the wild. Then, as we reached what seemed to be the top of the valley, Gerler started whistling, and I saw a black dot in the distant landscape ahead of us, which proved to be a yak herder's tent as we got closer. The occupants - two young men and a woman - came out and stared at us, and Gerler called out to them with a kind of Tibetan yodel.

Around the tent there were stacks of cut branches for firewood, and also a large mound of yak dung - presumably to be used as fuel for the fire. There was also a pair of very vicious barking dogs - Tibetan mastiffs - tethered up to a wooden bar outside the door of the tent. The dogs were going crazy, working themselves up into a rabid frenzy at the sight of us. I prayed that the chains used to tether them would not snap.

"This is my brother's tent," said Gerler. "We will stay here for tonight."

It was a blessed relief to dismount from the horse and to be able to walk around and stretch my numb and aching legs - I hadn't realised how saddle sore I'd been until I got off. I stepped warily around the barking dogs and we were ushered in through the doorway of the dirty black yurt-like tent.

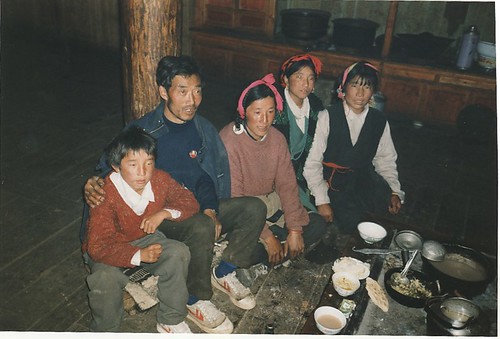

Inside, when my eyes adjusted to the dark and smoky interior, I saw that the tent had a earthen floor, pressed smooth and dry by constant pressure from the tent's inhabitants. The layout was centred around a fire, on top of which sat an iron frame holding a large sooty black cauldron. There was a hole in the tent roof immediately above the fire to let the smoke escape, but this was not a very efficient ventilation system. Quite a bit of smoke lingered in the tent, forming a grey-blue layer that sat above waist height. All the more incentive, then, for me to squat down on one of the several greasy hard cushions on the floor to get a bit of clear and clean air. When I raised my head too high it pierced the smoke layer, provoking an instant bout of coughing and giving me bloodshot eyes.

So I squatted on the floor and looked around me. The sides of the tent were packed with sacks of what looked like straw or twigs. There were also some pew-like low wooden benches, on which there were some dirty rolled up mattresses, and I presumed these were the cots. A few kitchen utensils were hung up around the fire - a ladle, a few metal pots, and a poker. And the five humans now inside the tent now shared the interior with several yak calves that were herded into one corner and kept in place by a rope as they scuffled and peed.

I was glad to be near the fire. It was almost nightfall and the temperature had plummeted to freezing. The weave of the yak hair material of the tent was quite loose - leaving gaps that looked big enough to poke a stick through. Nevertheless, it seemed to act as a block to the wind, and also stopped much of the rain that now seemed to be falling.

I started to unpack some bits and pieces from my backpack and soon had an array of billy cans, cups, bowls, knives and forks and packets of food arranged them around me, which proved to be utterly fascinating to the Tibetans. They watched as if mesmerised, as I used some boiling water from the cauldron to make up one of my dehydrated sweet and sour chicken-with-rice meals in a bag.

It all seemed so much more fussy than their simple fare of potatoes and noodles boiled up in a large pan. The Tibetans spoke their own Kham dialect, which I did not understand, although I was able to tell Gerler a few things about myself and my Auckland home, which he translated for the benefit of the others. They passed around the few pictures I had brought, uttering admiring cooh and ahhs as they fingered pictures of the beaches of New Zealand. Gerler told me that our Tibetan hosts were about to strike camp and move back down the valley to lower altitudes for the winter. This was their summer pasture, he explained, and in the first few days of October the weather was becoming too cold for the yaks. The young female Tibetan woman spoke quickly and melodically to the others, and they told me she said she had been working in the wool factory down at Laoyulin until it shut down. Now she was out of work, and there was little else to do but go back to herding yaks again.

It got dark and the Tibetans started to talk quietly among themselves, no doubt catching up on family gossip. One of the young guys produced a cassette player from somewhere, and they played a few wonky tapes of Chinese karaoke music as we sat in the dark. They smoked, took a swig or two of baijiu from a bottle, and we sat around the crackling fire.

By 9pm it was time for bed, and I decided it was way too cold to be sleeping outside in my microlight tent. Instead, they arranged a couple of old rugs on the earth floor for me, and watched again in fascination as I unpacked my sleeping bag and Thermarest and prepared for bed. They were gobsmacked when they saw me taking out my contact lenses, and asked me what part of my eye I had just removed.

I settled down in my corner of the tent, with a puppy tethered near my feet and the yak calves huddled just a couple of feet away, still peeing, and giving off a very distinct bovine aroma. And thus I fell asleep, despite my thirst caused by the smoky atmosphere of the tent.

Trek Day 2: Djesi Pass -Yulongxi

It snowed overnight, but I slept surprisingly well on the floor the yak herder's tent, thanks to my Thermarest. When I went out of the tent the next morning I was amazed to find myself in a snowy landscape, with clear sky revealing many icy peaks that I hadn't been able to see with the low mist the day before.

The early morning sun lit up the tips of the peaks with orange rays, and as I stamped my feet and pounded my arms by my sides I pitied the horses and yaks for having to have stayed outside overnight in such icy conditions.

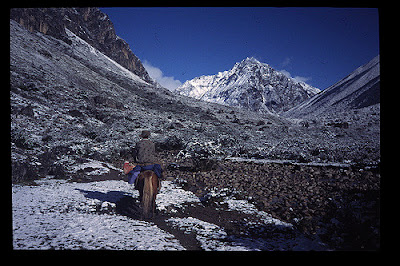

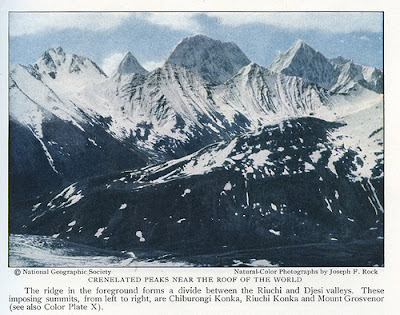

I made some porridge for breakfast in the tent, and my hosts made butter tea and rice porridge. Then we saddled up and were on our way up the gentle incline of the valley again. Ahead of us there was a neat pyramidal peak, which Gerler told me was called Jiazi Feng - Rock took a picture of the same peak and called it Chiburongi.

We plodded through the brilliant white landscape of the valley and saw more snowy peaks both ahead and behind us. We were approaching the Djesi La pas, but first the valley assumed a Y-shape, and our horses took us up a trail to the right hand fork. I was glad to have a guide with me as I would have become hopelessly lost at this point.

At the top of the 'pass' we entered another Y-shaped valley, and I saw the left arm headed into the midst of the snowy peaks and looked like a very lonely and desolate place to be. This must have been the Riuchi valley, which had been explored by Rock almost as an afterthought to his visit to Minya Konka. He described it as running almost parallel to the lower inhabited valley, and running directly into the mountain peaks. How I admired Rock's daring at this point. I couldn't imagine anyone venturing into that wilderness by themselves, especially at a time when there were no maps of the area. Interestingly, Rock also notes that it is these lower snow peaks of around 20,000 feet in altitude that can be seen from near Kangding - not Minya Konka itself, as many people falsely believe.

As we ascended it became colder and the biting wind blew harder. I had to put on my jacket and pull down the earflaps of my cap. There was a small amount of snow underfoot, but nothing to stop us crossing the pass. And there was still wildlife up at these high altitudes - I saw a flock of grey doves, a black flycatcher-like bird, and there were a few bluebell-like flowers poking out of the snow. We bore to the left in this plateau valley, and soon the tip of what must have been Gongga Shan came into sight - a most impressive and daunting vista. Behind us now all we could see was range after range of snowy peaks. We were well and truly into the Minya Konka massif, and approaching the crest of the pass.

With Gongga Shan passing in and out of view our horses jigged up to the flattish summit of the Djesi La, marked by the usual cairns, Mani stones and prayer flags. I wanted to stop and take photos but Gerler hurried me on, saying that we had a huge distance to travel today. We dismounted and led the horses down out of the snowfields and into a long, curving valley, which seemed very green but was absolutely deserted.

In 1929, Rock had encountered deep snow on his first, northbound, traverse of the Djesi Pass.

"Our mules and horses suffered terribly as they floundered belly deep in drifts," he wrote. "On the north-eastern side of the pass the snow lay still deeper. Our yaks, however, seemed to enjoy the situation greatly: although fully laden, they would lie down in the snow as if it were the most comfortable place in the world! These yaks and their owners seem to be kindred spirits. They behold the same dreary landscape, bare hills, and grassy valleys; endure long winters and short summers, with no spring or autumn to speak of. Ignorant of the outside world, these people seem entirely contented with their hard lot. They are born, live and die, not only in the same skin, but, one might almost say, in the same clothes, with those insect associates from which the Tibetan is never free. The minute a nomad enters a room, the air smells of yak butter, sour milk and yak dung smoke, to say nothing of the fragrance peculiar to an unwashed Tibetan himself."

Heading downhill beyond the pass, I felt a sense of exhilaration - the green landscape, surrounded by white peaks and topped by the blue sky was utterly beautiful and other worldly. And there was something mesmeric about the tinkle of the horse bells. As we walked on for hour after hour I began to think I could hear voices in the distance. I looked around but we were still all alone in this desolate valley. Then I imagined I could hear faint music or singing coming from somewhere - but again it seemed to be an auditory hallucination. When I stopped and listened hard the only sounds were the horse's bells and the wind.

Gerler set a relentless pace, and it wasn't until late morning and we reached lower down in the valley that he relented and allowed us a brief stop. We halted near a small stone wall shelter, in the lee of which I tried to get my hexy stove lit to brew some water for a cup of tea. While I was still faffing around with my lighter, Gerler gathered together a few twigs and sticks of wood, and soon had a vigorous fire burning that put my weedy flame from my fuel tablet to shame. Within a few minutes he had water boiling in his blackened pot and threw in a few lumps of brick tea to make 'Da-Cha' - a surprisingly thick and pungent form of green tea.

He also gave the horses a break, taking off their bridles and saddles, after which they harrumphed and rolled about on their backs in the grass, as if to rub their itchy manes. Then they wandered off to graze the fresh and untouched grass. When it came time to set off again they were reluctant to leave and we had to chase them up the hillside, panting for breath in the thin high altitude air.

He also gave the horses a break, taking off their bridles and saddles, after which they harrumphed and rolled about on their backs in the grass, as if to rub their itchy manes. Then they wandered off to graze the fresh and untouched grass. When it came time to set off again they were reluctant to leave and we had to chase them up the hillside, panting for breath in the thin high altitude air.It was near this spot that Rock had also paused near a large cairn to take photographs of Minya Konka. He had climbed up the side of the valley to a spur at 16,500 feet, from where Minya Konka appeared as a triangular peak, “not unlike one of the pyramids of Egypt."

As we continued on down, the weather ahead of us didn't look too good. Further along the valley we could see sheets of cloud dumping grey curtains of rain in the lower valley. As we set off, the clouds reached us and it started to snow lightly. The weather seemed to make the horses unsettled and mine started playing up as soon as I got back in the saddle. Gerler was in a hurry and started flicking his mount with the rope and trotting off ahead at high speed. Mine followed, but in a wild gallop that threatened to unseat me. I reined the horse in but Gerler urged me to keep up, and gestured at me to whip it with my rope. When I did so, the horse went berserk, cantering off at hair-raising speed, and before I knew what had happened I was thrown off to the right hand side and landed on my elbow in a pile of yak shit.

I was badly winded, but luckily nothing was broken except my camera strap. I wiped myself down and quickly remounted, thanking my lucky stars that the fall had occurred in a turfy area and not on one of the rocky patches of ground. I wouldn't want to break an arm here, two day's travel away from the nearest hospital.

We carried on down the dark and increasingly boggy valley, past a few cairns and some prayer flags. Up ahead I saw some small animals hopping about and thought they were rabbits. Then as we got closer I saw they were vultures, very scraggy creatures that were flapping around and squabbling with each other over the carcass of a crow. They didn't seem at all nervous of humans as we passed them.

As if this was an omen of bad luck, I was soon thrown from my horse again after it bolted in response to Gerler's cries to speed up. Once again I was shaken, but lucky not to break anything. This time I refused to remount immediately, but walked alongside for a while, which made me realise what a fast pace the horses were making compared to human walking speed. It wasn't long, though, before Gerler urged me back into the saddle.

Behind us a menacing dark grey cloud loomed over the pass, its wisps of vapour spilling over and curling towards us like tentacles, as dramatic as anything in a Steven Spielberg film. I remounted and we hurried along, but we could not outrun these scudding clouds. Soon we were completely enveloped in a grey-out and could barely see a few yards around us. It started to snow heavily, the tiny hard pellets of snow stinging my eyes, so I dismounted and started to walk. Gerler hitched the two horses together and lead them through the blizzard, but the one behind (my horse) panicked as he adjusted the straps and pulled away violently, snapping the tether. The horse went beserk, bucking like a bronco and trying to shake off its load of saddle and my backpacks, and then ran off into the mist and was soon engulfed in the grey murk. Oh great, I thought. My horse has just bolted and taken my gear with it. Here we are, stuck in the middle of oblivion in a snowstorm, and I have nothing but what I am stood up in.

Fortunately, the blizzard-cloud soon blew over, and the mist lifted almost as abruptly as it had enveloped us. The errant horse came into view, cantering in a circle around us, still spooked, but now a little less wild. It galloped towards me as if intent on running me down. Gerler leapt towards it as it passed, grabbing the rope and pulling in the reins, until it had been brought under control.

Crisis over, we continued on foot down the valley into clearer skies, but the little storm episode had left me exhausted and uneasy. We aimed for a spur, around which we descended in a narrow defile into another wider valley. There was still no sign of any other people.

As we plodded on through the relatively milder climes of the lower valley, Gerler became talkative. He asked me about the costs of cattle and sheep in New Zealand. He told me he had 60 head of yak. Did we all have guns in New Zealand?. You needed to have a gun if you were a yak herder, he told me, because there was so much cattle theft. He knew a lot about this because one of his brothers was a policeman. Another was a driver who plied the route to Lhasa and back. The rest of his brothers and sisters were yak herders in Lao Yulin.

He kept up a brisk walking pace, and told me we had to crack on as it was imperative that we reach the village of Yulongxi by nightfall. It was now mid afternoon and we still hadn't seen any sign of other people or any buildings. We passed a roofless stone shelter, where Gerler said he had camped on a previous trip he had made, as one of several guides accompanying a group of nine Americans with twenty horses.

As we reached more level ground he urged me to remount, but almost straight away the skittish horse bolted again, bucking wildly and throwing me onto a patch of stony ground, and leaving with a badly grazed and bruised right hand. Then Gerler did what he should have done right at the start, he let me ride his horse, which was much more placid, to the point of being dull. I bumped along, nursing my sore hand, the other holding the reins and the red tipped end of the rope. Gerler struggled with my restless horse and we continued on round another spur, and saw our first signs of human life this side of the Djesi pass - a dirt track and a stone house.

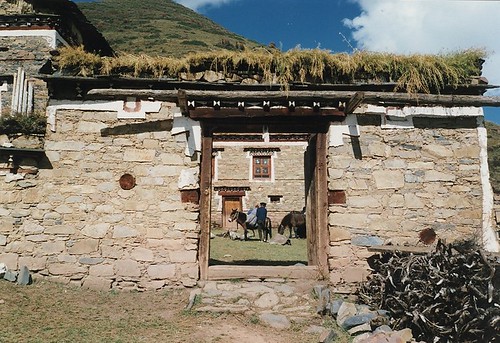

Although it was a plain and simple building, what a pleasant sight it seemed after a whole day of desolate valley. There were yaks and sheep grazing on the grassy slopes of nearby hills, and the scene reminded me of the wilder corners of the Yorkshire Dales, with the dry stone walls and grey stone buildings. Soon we saw another such house, and Gerler told me we had reached the upper reaches of Yulongxi, where we would be staying for the night before crossing the ridge over to the valley containing the Gongga monastery.

I was now exhausted and tired after a day spent walking and in the saddle, but to my frustration by early evening we still weren't there. Finally, just after 7pm, Gerler pursed his lips and pointed his chin over a fast flowing river. I didn't fancy fording this on horseback, so he led us to a place where a couple of logs had been thrown over the rushing water, and I was able to wobble across them to the other side.

Gerler stayed in the saddle and led both horses across, the waters coming up the horse's flanks to his knees. Soon we were stood outside the walls of a large Tibetan house, and Gerler was calling out, shouting to the occupants to let us in.

When the wooden door-gate was dragged open and we entered the courtyard I almost collapsed with fatigue on the steps of the house doorway. We were welcomed by a cousin of Gerler, who helped him take off the saddles of the horses and remove my pack, allowing the horses to bray and roll around on the grass and mud of the courtyard after their long haul of the day.

When Joseph Rock first arrived in Yulonghsi - as he called it - from the south, he stayed at a house that had once been the home of the late king of the Chiala region. In 1929 it was occupied by a local chief, a 'good natured Tibetan' called Drombo, who welcomed Rock and acted as his somewhat reluctant guide for the brief period of his first visit.

The house we stayed at was no palace. It was built in the style most Tibetan dwellings, with the ground floor used to house the animals - some young yaks and a pig sty located beneath the long drop toilet, from which the pigs greedily and noisily devoured the human droppings. From the dry mud surrounds of these animal rooms we climbed up a notched log to the first floor, which housed the extended family. It was very dark inside, and everything was wooden. The large room was centred around the open fireplace, where everyone sat around on dirty hard cushions or small ankle-high wooden stools. The few windows were shuttered or blocked up with thick polythene sheets, and there were just a couple of candles for light. The house was supported by thick wooden beams, but the Tibetan's skills in woodwork did not seem to extend beyond the walls and floors to furniture.

Apart from the tiny stools there was no other furniture, apart from some low tables to hold food and stores. As I squatted around the fire, the other family members were oblivious to my presence. There were two younger Tibetan women, both in traditional Tibetan skirts and with tanned, hard-working faces. They looked poor, and I mused on how land similar to this in the Yorkshire Dales would support a farmer in relative affluence of tweeds and a Land Rover, but here the same land was literally dirt poor.

Gerler's cousins got the ladle out and poured some of the smoky-flavoured water into my bowl so I could make some dehydrated lamb and vegetable rice dish, while they slurped their boiled noodles and the obligatory tsampa and butter tea.

Gerler told me that we would have to be prepared for some serious exertion and climbing the next day, as we would go over the steep Tsemi Pass to reach the Gongga monastery. I started to have second thoughts. I was already worn out from my efforts of today, and wondered if I might have a rest day tomorrow, or even just stay in this valley and continue down to Liuba instead. Gerler, however, insisted we had to press on. He wanted to get in and out to the Gompa, so that he could return home.

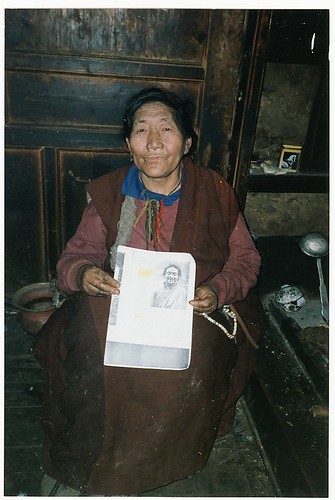

After dinner I felt a little better and passed around some of the old photographs of the Minya Konka area taken by Joseph Rock. One of them was a portrait of a local chief called 'Drombo'. The old lady of the house got quite excited when she saw this and told me "This looks like my father when he was young".

Anticipating another strenuous day, I had an early night. This time I had the relative luxury of a flea-ridden yak hair blanket on which to lie on, and I was able to settle in a dark corner with my water bottle handy this time to quench the seemingly ever present thirst and dry mouth and lips that I had at this altitude.

Trek Day 3: Yulongxi valley - Tsemi village

When I woke up in the Tibetan house in Yulongxi on Monday 25th September, 1995, I was a little bit puffy eyed and stiff, but as soon as I looked outside I was raring to go. The sight of the blue skies and the white snowy peaks dispelled my previous day's impulse to 'bug-out' to the nearest road. Now I wanted to go to Gongga Si. I had Coco Pops and Earl Grey tea for breakfast and then had to wait around impatiently for Gerler until mid morning. He wouldn't leave without getting a re-supply of cigarettes before we headed off into the wilderness over the Tsemi Pass.

At 10-ish we saddled up and started initially to head down the valley, southwest, in the direction of Mudju. I was still very uncomfortable in the saddle and had to shift around constantly until I could find the least uncomfortable position.

After about an hour's ride, we forded another shallow river, passed a few yak herder's tents (one of which had a large pile of yak dung beside it) and started to head up a side valley leading up to the ridge.

As we went up we entered a realm of sweet-smelling flowers and singing birds. The weather remained pleasant and I was feeling more confident in the saddle. The horse slowed down to a slow plod as the gradient increased, but even at a plod it was certainly better than walking up. It was a long, slow trek up to the pass, and I still had a niggling fear in the back of my mind about the track ahead, as Gerler said we would have to climb very high and cross the 'Da Xue Shan' (Big Snow Mountain) to get to Tsemi.

I needn't have worried. The going was easier than I thought - well, at least on horseback. We stopped for morning tea just before we reached the pass and I lay on the grass enjoying the sun on my face after brewing up some water to make a cup of instant vegetable soup with croutons. My face was sunburnt, my lips were dry and cracked and the backs of my hands were also very red and burnt.

When Rock had first come to Yulongxi, he had followed a similar route up to the top of the ridge in the hope of seeing Minya Konka. He was guided by the local headman Drombo up this hillside, but the Tibetan was worried about the deep snow and 'kept up whining laments', according to Rock.

We carried on, up through rockier terrain, towards the snow line. The horse was really struggling now, and I felt quite guilty getting a free ride. Gerler lit up a cigarette and started singing Tibetan folk songs, his ululating voice echoing off the rocky walls around us. And in no time we came to the snowy flat section that was the Tsemi Pass.

As we crested the last bit of track, Gongga Shan came into view - and what a magnificent sight it was. We were fortunate to have great weather and an almost completely clear sky, giving us a perfect view of the massive peak rising up across the other side of the valley, and the large glacier that swept down into the side valley.

Joseph Rock's first impression on seeing Minya Konka was ecstatic:

"And then suddenly, like a white promontory of clouds, we beheld the long hidden Minya Konka, rising 25,600 feet in sublime majesty. I could not help jumping for joy. I marvelled at the scenery which I, the first white man ever to stand here, was privileged to see."

We stopped and dismounted and, like Rock, I was so impressed I wanted to jump for joy and shout "La Rgellah!" - so I did. There was an amazing view of the array of peaks that made up the Minya Konka range, and the views down into the valley were also quite dizzying.

The valley was called 'Buchu' by Rock, who also details the many other subsidiary peaks surrounding, most rising to heights of around 20-22,000 feet, with names such as Nyambo Konka, Longemain and Daddomain.

"The scenery was superb. In fact, words fail to describe this marvellous panorama," Rock wrote.

But Rock did not cross the pass on his first reconnaissance visit up from Yulongxi. He thought the weather was still too cold in early spring, so he went back down and continued on his way to Kangding for the time being, to wait for milder weather. It was only on his return from a two week sojourn in Kangding that he made the crossing of this pass, accompanied again by Drombo and another local Tibetan from Yulongxi, called Jumeh.

We left the pass and headed down the track into the Buchu valley. Going down in an elated frame of mind, we followed the zig-zagging track and entered a sanctuary of natural beauty. There were rhododendron bushes and spruce further down. Birds flitted in the undergrowth and the warm sun warmed our faces. It really was an idyllic spot.

As we descended we gradually lost sight of Gongga Shan again, and it was only when we reached the Tsemi valley that I realised exactly how high up we'd been on the pass.

As we walked down the steep track I had to be very careful where I put my feet. At one point Gerler pointed out a steep drop off the track and told me this was where one of the Americans he'd guided had slipped off the track. "He broke his leg and was in such great pain he cried like a baby," said Gerler. "We had to strap him on a horse just like he was a sack and take him back to Yulongxi and out to Liuba to get him to on a truck to hospital in Kangding," he added.

We eventually reached the bottom of the valley, where we found a beautiful meadow and a fairytale village of sturdy stone Tibetan houses, the T-shaped window frames finished in pretty bright colours. It was all set amid pine-clad slopes and next to a gushing river, with the snow peaks in the background. This was Tsemi, and it seemed too good to be true.

We stopped for the night in Tsemi, but the dingy interiors of the Tibetan houses there were just the opposite of the beautiful outside environs. The house we stayed at was gloomy and filthy. I was again ushered upstairs onto the first floor to sit by the fire, while they stir fried some potato slices to make chips. I ate a few of these in the local fashion, with some chilli powder, but started to feel sick. Then as I became more accustomed to the dark surroundings I saw the eating bowls were crawling with flies and weevils, and there was a piglet snuffling around, sticking its little snout into all the plates and bowls as well. The floor was gritty and sooty, and the water they gave me to drink also tasted smoky and had small bits of grass and dirt in it.

The local people of Tsemi were a curious bunch in all respects. They crowded around the windows and doorways to get a peep at the foreigner. They were friendly and smiled at me, and oohed in aahed to each other in their own strange form of speech that sounded sometimes more like yodelling or singing than talking. It was a very secluded place and they still had busts and pictures of Chairman Mao on the display and old muzzle-loading musket hung up on the wall - and not as a relic, but as a working rifle for hunting.

Rock says little about Tsemi village in his article. He passed through, but only notes that it lies in the Buchu valley, near the junction of a side valley that contains the glacier running down from Minya Konka - and the mountain's monastery, or Konka Gompa as it was known to Rock.

"For six months in the year this monastery is shut off even from that remote world represented by the yak herders of Yulongshi, for the Tsemi Pass is snow bound and impassable," he notes.

I didn't sleep well in Tsemi, partly because of my stomach worries, but also because I had an almost sub-conscious feeling of being trapped in this valley. Gerler had repeated the concern that Rock had expressed in his article - that if we stayed too long we risked being trapped by heavy snows that could block the pass. I slept in my sleeping bag on a hairy mat on the sooty floor, and rose the next morning feeling terrible. I hadn't had much sleep and felt listless and jittery. I went through the motions of making breakfast, but had to repeat the whole tea-making process when I found a fly in the water I was boiling. I was already extremely weak and tired and just didn't feel up to the journey to the monastery ahead.

When I climbed into the saddle at 9am I felt like I was going to faint. We'd gone only a few hundred yards when I told Gerler to stop, and that I wanted to go back. I just didn't have the energy to go on. He took me back inside the hose and plied me with some butter tea. I wanted to retch when I first put it up to my lips, but at Gerler's insistence I drank the muddy brown and salty liquid sip by sip until I'd finished the bowl.

When I told him that I was worried about my health and wanted to go back over the pass to Yulongxi, he refused. "It is my duty to take you to the monastery and that is what I will do," he said solemnly.

After another bowl of butter tea I started to feel a lot better - it was almost like a miracle cure.

"When you go on a journey like this you must drink lots of this tea," said Gerler. "You need lots of energy. I don't think this western food is very good for you," he added, pointing with his chin to my packet soups and dehydrated meals. I had to agree with him.

"Come on, try again," he said. "It's only about two more hours to the monastery."

Still feeling a little queasy, I agreed, and this time I walked alongside the horses for a while instead of riding. We crossed a meadow in the sunshine and then crossed a large creek by a wooden bridge, following a track up through a magical forest of beech.

The track went up, passing lots of Mani stones and cairns, and the whole place had a very spooky atmosphere about it. There was an almost physical presence in the woods, and I could feel we were nearing a special place. Even the horses seemed to be possessed by a new spirit, and raced each other up the track. Birds were singing, a stream tinkled by below us and there were fresh mushrooms and fungi growing along the track. After an hour or so we reached a fork in the rack, with the left hand pathway going back towards Kangding, according to Gerler. This track would go down to a place called Riwuqie, he said, the other branch of the Y-shaped valley we had gone through on the way up to the Jezi La. We did not travel along this route because it was higher and more snowbound than the longer but passable Yulongxi route.

A short way ahead our horses stopped to drink from a water trough, and as we rounded the corner and emerged from the forest I saw some small stone outhouses and realised that we were finally there - we had reached the Gongga Si monastery. The monastery's whitewashed walls appeared above the bushes, and I was thrilled to see that it looked just like the building in Rock's old photographs.

Trek Day 4: The Konka Gompa

There was nobody at home at the Konka Gompa monastery when we arrived. The wooden door in the side of the wall was bolted shut and when we peeped through a gap, all we could see was a dog chained up against a wooden banister. No sounds could be heard, except the flap of prayer flags in the wind and the trickle of water along a primitive guttering channel that diverted a ribbon of water from a small mountain stream.

Gerler called out in Tibetan and after a few moments there was a faint, distant reply from somewhere beyond the monastery. We turned around and saw a tiny red and yellow-clad figure ambling down the hillside towards us. It was a dwarfish lama and he was carrying a sizeable bunch of sticks tied onto his back. When he arrived, he dumped his load of firewood at our feet and nodded at me in recognition, as if he had been expecting us and as if foreign visitors to this remote monastery were an everyday occurrence. The little shaven-headed lama bade us welcome and unlocked the padlock on the door, gesturing for us to go into the courtyard. He wasn't one to stand on ceremony - he helped us unstrap our bags from the horses and take off the saddles, and then he led us into his smoky, soot-stained scullery.

Gerler called out in Tibetan and after a few moments there was a faint, distant reply from somewhere beyond the monastery. We turned around and saw a tiny red and yellow-clad figure ambling down the hillside towards us. It was a dwarfish lama and he was carrying a sizeable bunch of sticks tied onto his back. When he arrived, he dumped his load of firewood at our feet and nodded at me in recognition, as if he had been expecting us and as if foreign visitors to this remote monastery were an everyday occurrence. The little shaven-headed lama bade us welcome and unlocked the padlock on the door, gesturing for us to go into the courtyard. He wasn't one to stand on ceremony - he helped us unstrap our bags from the horses and take off the saddles, and then he led us into his smoky, soot-stained scullery. There, he immediately got some boiling water from the cauldron and started making butter tea. He did this by pouring the steaming water into a long wooden tube, followed by some yak butter and tea leaves, and then he pushed a wooden plunger in and out with great sucking and squelching noises, to mix it all up. It's a familiar routine in any Tibetan household.

I just felt so elated to actually be in this place at long last. I thought back to the first time I had read about this tiny monastery in one of Rock's articles, several years previously back in Auckland, and now here I was, in the very spot. And even more surprisingly, the place seemed to have barely changed from how Rock had described it.

"We were escorted into a square house, having a courtyard filled with mud, and up over an old sagging stairway to a balcony which led to a chanting hall and a narrow room with a chapel on one side. A small window overlooking the glacier valley permitted a perfect view of Minya Konka under favourable weather conditions."

As we sat around the fire, I showed the lama some of Rock's photographs of the gompa and its surroundings, and he recognised the old building, which had been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. The present monastery building had been rebuilt in the same style during the 1980s, he told me.

The lama, whose name was Ding Ri Zhu, also recognised Rock's photo portrait of the headman of Yulongxi, Drombo, and he pointed to a picture Rock had taken of a wall painting of the mountain god, Dordjelutru, and said that the painting was still here.

After he finished his tea, the lama took me on a tour of the monastery. He didn't speak Chinese, so I couldn't understand what he was mumbling about when he showed me the various draughty guest rooms and dusty storage rooms. The lama told me that on special occasions they had 20-30 monks come up from the lower monasteries in places like Liuba to put on special ceremonies for the mountain gods.

I asked him if it was true, as Rock had claimed, that the monastery was cut off by snow on the passes from November through to April, but he said this was only the case during very heavy snowfalls. It was still possible to get over the pass during the winter months, he said, and it was also possible to walk out in the opposite direction, down the valley to Hailouoguo and Moxi on the eastern side of Gongga Shan, he added. So much for Rock's claims of a monastery cut off for half a year in its isolated mountain fastness!

The lama showed me the gompa's small chanting hall, with its golden statues and the bright murals of fierce-looking Tibetan Buddhist deities that were portrayed as surrounded by skulls and bolts of lightning.

He then took me into a small, gloomy back room and lifted up the edge of a cloth hanging on the wall, to reveal a picture of the mountain god Dordjelutru, similar to the one photographed by Rock.

This was obviously one of the most sacred relics in the monastery, and the monk seemed to expect me to be very impressed by it. However, I found it hard to be very reverent because the picture was much smaller than I'd anticipated - it was only about a foot wide and three feet long. From Rock's picture of it I had assumed it would be much bigger, covering a whole wall.

Rock described an inscription that accompanied the portrayal of Dordjelutru:

"On the gate to the chapel in my room hung a long strip of hempcloth with a Tibetan inscription. It declared that there is no more beautiful spot on earth than Minya Konka, and that one night spent on the mountain is equivalent to sitting ten years in meditation in one's house and praying constantly; that one offering of burning juniper boughs [here] is equivalent to hundreds of thousands of prayers."

The inscription also said that the Indian founder of the red hat (Karmapa) branch of Buddhism had pronounced that this god, Dordjelutru, was the equal of the prime deity Shenrezig, and that all the deities of Tibetan Buddhism dwelled within this scared mountain "and anyone gazing upon the peak will have all his past sins wiped off the slate so he may begin life anew!"

After lunch that consisted of chicken broth taken in the dirty scullery, I wandered around and snapped away with my camera, trying to take pictures from the same places as Rock had taken them. Unfortunately, the low cloud had really closed in around the gompa, and there was little to see of Minya Konka, whose summit and ice ridges remained hidden in the mist just above us. All we could see was the foot of the glacier moraine.

The little lama scurried off into one of the back rooms and before long we could hear him chanting away continuously in the background, occasionally banging on a drum a few times, or ringing a discordant little bell.

In contrast to these displays of piety, I busied myself with some mundane housekeeping tasks. To the accompaniment of chants and gongs I washed my smoke and soot-laden hair using the little sachets of Head and Shoulders that are sold in strips in rural Chinese stores. Then I set about scrubbing my socks and undies in the trickle of water from the mountain stream, hanging them up next to the prayer flags to flap in the breeze sending who-knows-what message skywards to the gods.

In the middle of the afternoon the lama re-appeared at the doorway of the gompa and gestured up at the glacier, from which some of the cloud and mist had receded slightly. He told me, via Gerler, that there was a special shrine located a little higher up the mountain, and he pointed his bony brown finger at it. I couldn't see anything, until Gerler also gestured at a small red dot among the snow and rocks. They both said it was a very special place where all the prayers could be said directly to the mountain god.It didn't look far, and having nothing better to do, I decided to go and have a closer look.

Taking just a small pack with my camera in, I set off down the slope into the massive gully that held the glacier, following a faint track that took me down to the glacier moraine. I kept looking up at where the shrine was supposed to be, but it was difficult to keep track of it because of the tree branches obscuring the view, and also because I lost sight of many of the reference points as I headed further down into the glacier valley. The shrine had looked quite close to the gompa, but I was to learn how distances can be deceptive at high altitudes - perhaps due to the thin clear air making everything look so vivid and almost close enough to touch.

I struggled for a couple of hours up the glacier moraine and got nowhere near the upper shrine. I was floundering about among the large rocks, still unaccustomed to moving at high altitude, and I was constantly having to stop to get my breath back. I didn't seem to be making any progress towards the shrine, and I began to wonder at what time I should turn back. This little problem was solved for me when I foolishly tried to cross a small glacial river. It was just slightly too deep to get away without swamping my boots, so I took them off and tried wading over in bare feet with my trousers rolled up to the knees. The icy cold water, fresh from the glacier, was shockingly cold - colder than anything I had very experienced before. The water was so extremely chilling that it felt like it was scalding my exposed skin wherever it came into contact with it. I skipped through the little river with just ten painful steps, but had to stop on the other side and sit down on a boulder, to rub some feeling back into my deep-frozen feet and toes. Now I suddenly understood just how easily it would be to die of exposure and hypothermia in waters such as this.

My little excursion up the glacier had left me tired, thirsty and disoriented, and so I turned back, disconsolate, to the return to the gompa. It was late in the afternoon by the time I got back, and I had to really struggle to climb back out of the gully of the glacier valley and to get back up to the monastery perched on the side of the ridge. When I looked back at how far I'd travelled, it looked like a 10 minute walk.

Back inside the gompa, I felt absolutely famished, and slurped down a quick cup of tomato instant soup. It tasted better than anything I could remember for a long time.

I passed the remainder of the day and the early evening sat in the smoky but warm little room that the lama used as a kitchen and living space. The lama showed me a collection of notes and postcards left by earlier international visitors - Americans, Germans, Japanese - mostly mountaineers, who had used the monastery as a base camp during their attempts on the peak. One such Japanese expedition had lost seven members killed in an avalanche near the summit. The lama brought out a plastic watch that had been given to him by one of the Japanese climbing team. He said the watch had been very useful, but now it had broken, and could I please fix it for him?

I took a cursory look and it seemed that the watch battery must have run out. Regretfully, I handed the watch back to the lama and told him that he would have to try get a new battery from a place like Kangding - if he or any of his fellow monks ever made it as far as the 'big smoke'.

After stir frying up some more potato sliver chips, the lama showed me to a bare wooden room that was to be my bedroom for the night. I got myself settled in, but something about the room unsettled me. I felt cold and claustrophobic - and just plain lonely. It had started to rain heavily and when I turned off my torch I found myself feeling terrified of the dark, like a child. After just a few minutes lying in the creepy blackness, I fled, picking up all my gear and moving back into the dirty smoky scullery where the lama and Gerler were still squatting around the fire.

I dossed down in a dark corner of the room and tried to sleep there, but without much luck. I would find myself dropping off to sleep, only to wake up after just a few minutes with a sudden start, because I had stopped breathing. Then I would start hyperventilating and also salivating so much that I was drooling. It was all very weird and worrying. I later learned that this could have been the medical phenomenon known as Cheyne Stokes syndrome, in which the lack of oxygen in the thin, high altitude air upsets the body's usual automatic regulation of respiration. I didn't know this at the time, however, and I believed I was simply unable to breathe properly, and that if I fell asleep I would just stop breathing and die in my sleep. I spent much of the night gazing at the ceiling, thinking about home, and how far I was away from everything.

Joseph Rock also spent an unsettled night at the Konka Gompa. He was given the chapel room to sleep in, which contained a golden chorten (shrine) encrusted with jewels. This sarcophagus contained the remains of a previous living Buddha of the monastery. Under the title of 'A weird night with a mummy for companion', Rock's article paints a dramatic picture of how he lay shivering in his cot as thunder crashed all around the mountain, rain lashed the monastery and lightning flashed as: "Dordjelutru staged an electrical display in this weird canyon".

"Here, all alone, in the presence of a sacred mummy in a hoary lamasery, I listened to the tempest breaking over the icy peak of Minya Konka. Was this the year 1929 or had time been set back a thousand years?" he wrote.

He may have been exaggerating, but now I could understand what inspired his feverish imaginings.

Trek Day 5: Returning via Liuba

The mountain gods were eventually kind to Joseph Rock. After his stormy night in the Gompa, the weather cleared the next morning, and he was able to set out and explore higher up the ridge. He reached a height of 17,200 feet, from where he was able to take a panoramic photograph looking back down into the valley, with the monastery visible as just a tiny patch on the side of the ridge. He was also able to take some excellent close up views of Minya Konka and its glacier.

Being a botanist, Rock also spent time collecting samples of the rhododendrons and other alpine plants, as well as documenting the area with his camera and its novel colour plates.

Almost sixty years later, in 1995, we had no such luck. We woke to find that while the skies had cleared somewhat during the night, Minya Konka was still stubbornly hiding herself, shrouded in clouds. In the cold light of dawn we also found that the valley below us had filled up with cloud, obscuring the hamlet of Tsemi far below.

Gerler was up early and he was impatient to leave. After a quick breakfast of rice gruel porridge, he had been chasing around the hillside, trying to locate our two horses. They had wandered off in the night after being put out to graze. It was only after much searching around and panting up and down the hillside that we were able to locate the horses, by the sound of their bells.

Back at the monastery the lama had taken up his interminable chanting again, but he broke off to come outside and see us off. After taking a last few pictures of him and the mountain (and assuring him that I would try help him get a replacement watch battery), he gave us a small wave and we set off, leading the horses back downhill on the track to Tsemi.

The sun was still only just coming up over the ridges, and its yellow rays were just touching the tops of some of the surrounding peaks. As we departed I looked back towards the gompa and saw the monk walking back to his lonely routine of chanting, and I felt a twinge of regret at leaving this isolated place.

We re-traced our steps back down the trail dotted by Mani stones, to Tsemi, with me hobbling along behind the horses because of the many blisters on my feet. I was also smarting from sunburn on my nose and the tips of my ears, while my lips were dry, cracked and I felt constantly thirsty.

Back down into the 'Buchu valley' we went, into the trees and crossing the small river by a log bridge. We passed through Tsemi again, but this time with only a brief pause, as Gerler was anxious to get back to Yulongxi as early as possible. On the other side of the hamlet we mounted our horses and set off to ride the trail up the hill to cross back over the Tsemi La pass.

It was hard going for the horses, with mine pausing for breath every twenty steps or so, and sweating profusely through its coat of hair. I felt so sorry for the old nag that I got off and tried walking for a bit, but I found myself tired out after just a few steps. Gerler urged me to get back into the saddle, and thus we continued on up, making good time and reaching the pass by 11.30am. There were no awesome views this time - the great mountain was still hidden by cloud, and we did not linger.

From the pass we dismounted and plodded back on down towards Yulongxi. Gerler started singing again, his wailing seeming to reach right across the valley.

It took us a couple of hours to reach the bottom of the valley, where we had to ford the river on horseback again. This time the river seemed to be even deeper, and both my feet and the bottom of my pack got a soaking. But by now I didn't really care. Then we were back amid the scattered settlements of the Yulongxi valley, and this was where I would part with Gerler. Rather than repeat the two day slog retracing our footsteps back over the Djesi la, I decided I would walk out in the opposite direction, west, to Liuba and the roadhead, from where I hoped to be able to get a bus back to Kangding.

As we sat down for a late lunch of soup and what remained of my Toblerone, I handed over 450 kuai in crumpled renminbi notes to Gerler for his services over the last five days. I felt quite sad to be leaving my trusty guide. He had been honest and reliable, and had gone the extra mile, pushing me to continue when I was wavering and feeling sick in Tsemi. My appreciation waned a little when he started to plead with me to give him several items of my kit that I "wouldn't be needing any more". Gerler was particular taken with my waterproof overtrousers, and I promised that I would bring some for him on my next visit. He wasn't impressed.

At 1.30pm we parted ways and I headed of down the flat grassy valley towards Mudju and Liuba. After only a short time walking alone, I soon realised how lonely and vulnerable I felt when travelling by myself. I had become used to the reassuring presence of Gerler, and his automatic introductions to people and places to stay along the way. Now I was alone and I became the subject of curious stares from the Tibetans I encountered in the small hamlets that I trudged through. Some of the stares were mute and uncomprehending, but other onlookers started questioning me in a tone that was mocking and aggressive.

"Where are you going?" they would ask.

When I said Liuba, they would snigger. "You alone?" I would walk on, picking up my pace. After being asked the same questions a few times, I started replying that I was with a group and my 'three friends' were not far behind, with our 'guide'.