Joseph Rock starts off his article about his 1926 expedition to the 'mountains of mystery' - the Amnye Machen peaks - with the now familiar litany of outlandish and colourful claims. It is a remote and unexplored region, he writes, forgotten by time and peopled by warlike and nomadic Tibetan bandit tribes who know nothing of the outside world. An arduous journey across bleak grasslands is needed to reach this unknown mountain, which he says is 28,000 feet high - "almost as high as Everest" (it is actually only about 25,000 feet in height).

His article continues in this vein for several pages, perhaps to make up for the fact that he achieved so little. His generously-funded and extravagantly mounted expedition did not get anywhere near the mountain, despite two years of trying. After floundering about in the gorges and canyons of the upper reaches of the Yellow valley, Rock only managed to get a glimpse of the Amnye Machen range from a distant mountain pass 30 miles away. This seems especially odd to the modern reader as these days the mountain is easily accessible and can be circumambulated in a few days by backpackers. The terrain in the immediate vicinity of the mountain is bleak but poses no particular deterrent to the competent and prepared traveller. So why did Rock spend so long faffing around in the labyrinths of the Yellow river gorges - especially (as he admits himself) the area is so disappointing from a plant collector's point of view?

Perhaps it is easy with the benefit of hindsight and the images of Google Earth at one's fingertips, to forget how difficult it must have been to approach Amnye Machen in the 1920s. The area had been visited earlier by several western and Russian explorers, but it was still very much an unknown region. The main barrier to any curious outsider must have been the hostile Ngolok tribes who lived in the area and who violently repelled any intrusions by outsiders. And yet Rock had already dealt with a similar situation when trying to visit his so-called "Holy Mountains of the Outlaws", the Konkaling mountains near Muli. This time however, the scale of the country was much greater, and his friendship with the wily Prince of Choni was of little use because the prince held no influence over the distant Ngoloks in another province.

Nevertheless, Rock took the advice of the Choni prince, who told him that the best way to approach the Amnye Machen mountain would be via the small monastery of Ragya (or 'Radja' as Rock calls it) on the upper reaches of the Yellow river.

With a commission and a large cheque from the Arnold Aboretum to conduct a comprehensive plant hunting expedition in the botanical 'virgin territory' of Amnye Machen, Rock set off in the spring of 1926. He didn't travel lightly. In addition to his 12 Naxi helpers, he had 34 mules and 60 yaks carrying five months of supplies. As if this wasn't enough, he also hired a mob of surly and cantankerous local Tibetan horsemen, known as 'Sokwo Arik' to act as a bodyguard on his journey across the grasslands from Labrang to Ragya.

This was also one of the few trips on which Rock took along another westerner. Although he doesn't mention him by name, Rock brought along the American missionary William Simpson "dressed in Tibetan garb", to act as a Tibetan translator. As already mentioned, Simpson had been working as a missionary in the Labrang area, but Rock soon found he disliked the missionary's "do gooder" ways and lack of firmness with the natives.

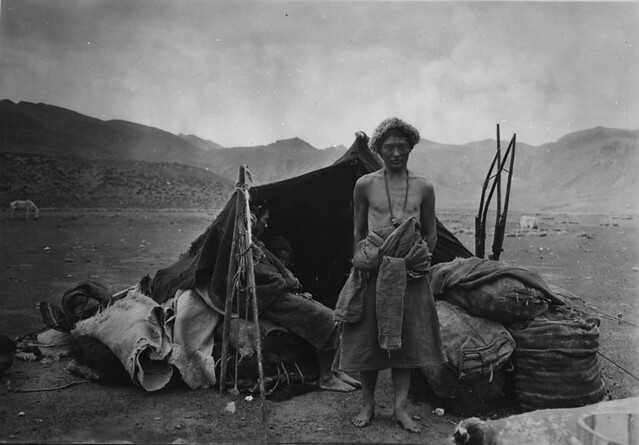

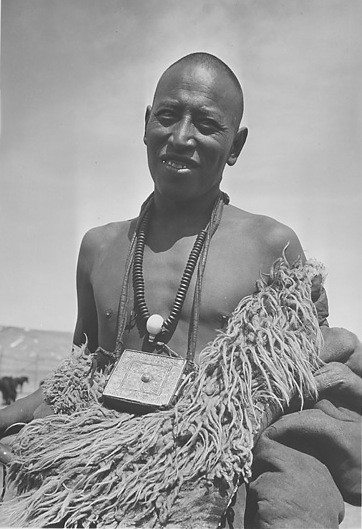

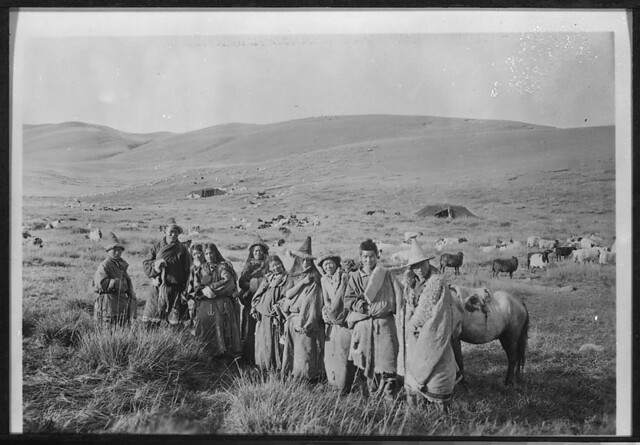

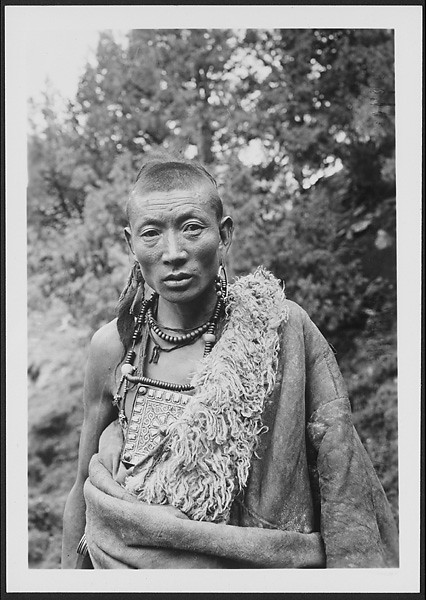

Their journey from Labrang to Ragya took them westwards over bleak and boggy grasslands, peopled only by a few itinerant nomads living in black yak hair tents. Rock's photographs portray the Tibetan nomads as wild and magnificent people, but in his writings he dismisses them as ignorant, superstitious and filthy.

On one occasion he looked on with disgust as an old woman pulled out a dirty bowl for him from on top of a heap of dung, wiped it with her filthy fingers and greasy clothes and then filled it with a hunk of yak butter that had the imprints of many other soiled fingernails scraped into it. Rock made his excuses to leave by saying that he had to take photographs outside.

According to Rock, this was a land that time had passed by - the local people had never seen a car or could conceive of a train. They had no concept of electricity or modern appliances and believed the world was flat. Things had not changed since the time of Marco Polo, he wrote. He played them records by Caruso and Dame Nellie Melba and they marvelled at the music produced by the "Urussu" (Russian) - their local word for all foreigners.

The landscape they travelled across was 'dreary' and disappointing, not just to the eye but also from a botanical perspective. So instead of plants, Rock noted the many types of wildlife in the region - marmots and pheasants, blue sheep and rabbits. There were tame birds that had never learned to be afraid of man. But there were also wolves, following the expedition caravan at a safe distance and watching them from the ridgelines.

From Labrang they passed through the Sang Chu valley, still littered with the bones of Tibetans slaughtered in a recent battle with the Muslims. Traversing grasslands dotted with the black tents of nomads, they crossed a 13,000 foot high pass - in a blizzard in June - to descend towards the Yellow River. The 'unruly' Sokwo bodyguard were then paid off to return to Labrang, "without a word of farewell or the slightest sign of interest in me".

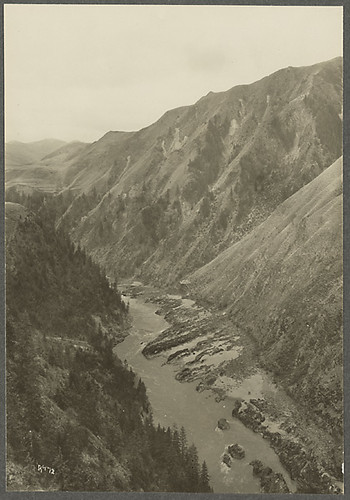

It is here that Rock makes another "first white man" claim - this time, to be the first to explore the steep canyons of gorges of the Yellow River, which he says are at least 3000 feet deep.

"It gave me a peculiar feeling in this lonely wilderness to be the first to look upon this mighty river flowing through hitherto unknown gorges," he writes.

After exploring several sheer-sided tributary valleys of the Yellow river and killing a pair of eagles ("now in the museum at Harvard"), Rock made a brief stop at a monastery called Dzangar, before continuing upriver to Ragya monastery.

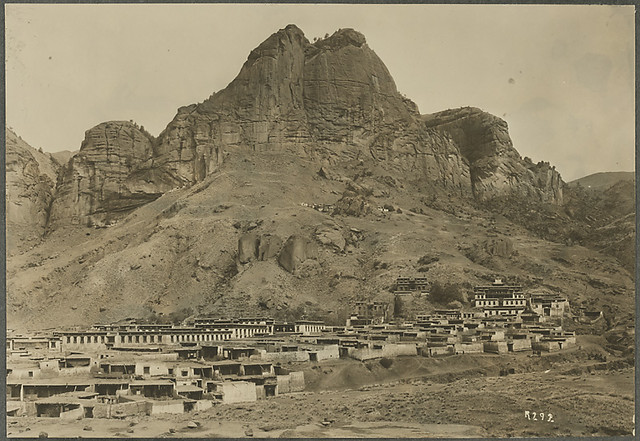

Once again he was both enthralled and disgusted by the extremes of a remote and secluded community. "Few in the outside world know that Radja Gompa exists ...Life here is unbelievably crude ..."

One of the strange things he encountered at Ragya was a room room full of clocks and timepieces collected by the Abbott of the monastery. It reads like a scene from a movie.

"From floor to ceiling, clocks and watches of every description and size were ticking away, each keeping its own time regardless of the actual hour. Clocks struck at various intervals, some in unison, others in quick succession."

Rock added to the collection with the gift of a watch.

After the long journey, Joseph Rock settled in to quarters at the Ragya monastery, and prepared for the next phase of the expedition - the approach to Amnye Machen though Ngolok territory. However, the officials of the monastery warned him against taking his expedition into Ngolok territory, saying the tribes would probably murder them. If he was to go, he must make a quick dash on horseback, before the Ngoloks knew of his presence, they advised.

Rock demurred and asked the lamas to send an envoy with requests to visit - and accompanied with generous gifts for the Ngolok chiefs. He had not come all this way for a brief visit, and he wanted to spend an extended period collecting plants and viewing the mountain. While waiting for a reply from the Ngolok, he explored the area around the monastery - photographing the stupendous cliffs under which it sat, and the tiny hermit residences on the hillside, where lamas lived on nothing but nettle soup.

He observed the daily lives of the lamas and again was scornful of their superstitious and feudal ways. One lama was observed 'printing' Buddha images on the surface of the Yellow river by slapping a board onto the water carved with a sacred image. "He occupied himself in this way for hours," Rock observes drily. Rock also recounts cynically how the Living Buddhas always seemed to be found among the offspring of families of high lamas and officials - how convenient!