After a decade of pondering and a year of planning to go to Choni monastery in Gansu, I was only able to spend about an hour walking round the place when I eventually got there in May 2012. This was because I was detained by the local police almost as soon as I got off the bus in Choni. Fortunately I’d gone straight to the Chanding monastery on my arrival in ‘Zhuoni’ (卓尼) as it is now known, and was able to spend a short time walking round the various monastery temples snapping a few pictures before I was nabbed by the Public Security Bureau. There wasn't much to see - the monastery complex was like a ghost town, with few monks in evidence and all the temples locked up.

Back in the 1920s, Joseph Rock had received a slightly warmer reception in Choni and had struck up a more cordial relationship with the local authorities. He befriended the local prince – the tusi – an ethnic Tibetan but Chinese-accultured herditary ruler who was the latest to succeed to the post that had been passed on for 22 generations since the 1400s. Even into the 20th century, the potentate ruled by grace of the Qing dynasty and its successors in the new post-1911 Chinese Republican movement. Prince Wang Chi-Ching, as he was known in Chinese, was a suave character who liked dressing up in Chinese silks and stylish Tibetan boots. He was both temporal and spiritual head of the small Tibetan enclave of Choni, acting as both prince and head lama. However, he was not an independent prince. He had to pay tribute, obeisance - and taxes - to the Chinese authorities and warlords who held sway in Lanzhou.

At that time, Choni was the cultural and political centre of this ethnic Tibetan corner of south western Gansu. Unlike most of the arid and flat province of Gansu, Choni was mountainous and fertile, with the river Tao river helping to irrigate rice crops and support a mixed population of Tibetans (known locally as Tebbus), Muslims and Han Chinese.

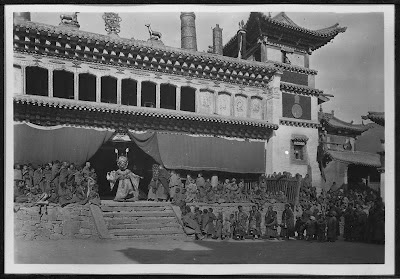

Joseph Rock’s pictures show a busy and active monastery of about five ornate temple buildings, and scores of resident monks involved in all kinds of strange ceremonies and rituals. Rock was so impressed with Choni that he selected it as his base for exploring the Qinghai grasslands - and it became the springboard for his ultimate visit to Amnye Machen. He was to stay at the Prince's Choni yamen (compound) almost two years from 1925-26, thanks in part to being on friendly terms with the local prince.

He describes the place briefly in his National Geographic article about his Amnye Machen expedition ("Seeking the Mountains of Mystery"), but writes a lot more about Choni in a separate article entitled “Life Among The Lamas of Choni”. In this latter article he describes the lifestyle and many of the customs and clothing of the local Tibetans in Choni. He spends most of the article describing the intricate and lengthy ceremonies of the local lamas, and also something of one of their major festivals.

Accompanied by many early colour Autochrome pictures of the Tibetan “devil dancers” at the monastery and their costumes, Rock's article gives a lengthy description of the annual Mystery Plays and Butter Festival ceremonies held at Choni. Some of the 'devil' dancers are dressed to look like skeletons, animals such as deer, as well as some traditional Buddhist deities and demons. One of the most interesting performers was a monk wearing a papier mache mask that looked something like the head of one of the ‘jolly Buddha’ icons.

This performer was meant to represent a oafish Han Chinese monk, Nantain, who was bested in debates by Tibetan monks, a figure of fun for the Tibetans who was the butt of many physical and verbal jokes and mockery during the comedic ceremony. It is all rather reminiscent of one of the modern day “cross talk sketches” as shown on Chinese TV, a kind of music hall act in which the characters exchange banter and mix this in with slapstick comedy and double takes.

According to Rock, the public mockery of the Chinese went down well with the Tibetan spectators, as there was little love lost between the Tibetans and Han Chinese at the time. The Han Chinese were heartily despised and the Tibetans loved to make fun of them.

However, there was also a darker side to the devil dances, with the Tibetan sorcerers supposedly summing up and exorcising demons. The scholarly Joseph Rock was skeptical and dismissive about the supposed effects of these devil dances, until he found himself severely disturbed during one such performance at the neighbouring Hochiassu monastery near Choni.

While watching the dances he noticed that some of the crowd of local onlookers appeared to have become possessed by spirits and were flailing about. Other spectators laughed at these possessed until they too became infected and equally manic. Rock and his missionarly companions then also started to feel queer. "I began to feel a bit uneasy ... and Mr McGilvrey felt terribly oppressed," Rock wrote later.

"At that moment I felt a most peculiar sensation, as if I was giving way to some unknown force, and I felt myself become powerless. I managed to say 'I must go, I cannot stand this' .. and left the chanting hall as quickly as I could."

He felt slightly better when he moved away from the devil dancers, but had a second 'attack' when he settled in a nearby room:

"I had hardly sat down when the powerless feeling came over me in a few minutes, and my sight was practically gone. I could ill distinguish things. I tried to repress this feeling and started taking deep breathing, but every second I felt myself going and I came to the conclusion that if I did not leave immediately I would be unconscious the next minute."

Rock only recovered when he had fled from the monastery, and was left shaken by his experience. Despite his self image as a man of science, he could only conclude that "There is a power or spell of some kind..."

"I may say that never in all my life have I felt in such a sudden manner my willpower and my control over my being leave me ... It was like filtering of something though one's body which took charge of one completely. It was the elimination of self and the control of self through another force, which I fought, but to which I would have sucuumbed. The lamas explained this as the god of the monastery taking possession of one's body."

Nevertheless, with the aid and hospitality of Prince Yang, Rock settled in Choni and installed himself in the yamen there while he prepared to mount his much-anticipated plant collecting expedition to Amnye Machen. And as a preface to his future anthropological and cultural studies of the Nakhi in Lijiang, he also made many observations about the customs and people of Choni. The monastery was famous for its library, which contained rare copies of the two major Tibetan classical sacred texts: the 108 volume Tandjur and the 209-volume Kandjur. It took a large team of monks about a year to print just one set of all these volumes, and Rock was able to buy a complete set and pack it off to Washington, where it was lodged with the Library of Congress.

During his time in Choni, Rock seemed to get along well with the sinicised and relatively 'modern' Prince Yang – going to him for advice about how to travel to Amnye Machen and even borrowing money from him when his funds from the US failed to come through on time.

However, like the King of Muli, Prince Yang could also be a cruel and despotic local ruler. He had several wives who he kept in servitude and with bound feet. One of them he had beaten severely after she tried to leave without his permission to visit her ailing mother. The wife hanged herself shortly afterwards

Even Rock acknowledged that Yang was a bad sort, noting that he was not popular with his local ‘subjects’. To maintain his grip on power the prince kept a network of spies and informers in addition to his own local army of enforcers. He imposed fines on the local people and 'squeezed' businesses for his own income. According to Rock, the prince was only tolerated because he was seen as a buffer between the locals and the even more hated Chinese.

My own journey to Choni started at Labrang (Xiahe). The locals told me there was no direct bus to Choni, but that I could catch a bus to the town of Hezuo an find one there. According to my map it was only about 70km to Hezuo and a further 100km to Choni, so I hoped I might do it in one day. I didn't want to have to spend a night in Hezuo - there didn't seem to be much there apart from a reconstructed nine-storey temple that Rock had photographed back in 1925, when the town was know as Hei Tso.

As things turned out, I didn't need to stop over in Hezuo. When our bus trundled into town mid morning it looked like any other nondescript scrappy provincial Chinese town - a mix of concrete high rises and garage-front stores. A friendly Tibetan sat behind me on the bus pointed out the street corner where I should catch the Choni bus, and I jumped off the Xiahe bus just as the Choni service was departing. I was able to flag it down and jump on without having to buy a ticket.

The ride to Choni took us over rolling dull grassland and a couple of gentle passes. There were a few Tibetan herder's houses en route, quite basic concrete blocks, but all of them seemed to have glassed-in 'conservatories' in front of the living areas. This seemed to be a standard feature of the Gansu-Qinghai grasslands.

Before we reached Choni the bus descended into Lintan, another scrappy town with a large Muslim population and many prominent mosques. This was the old "Taochow" that Rock had written about - but he never mentioned the obvious Muslim character of the town. After a tedious hour long wait during which time I attracted many stares from bemused locals, the bus started up again and took us the final hour's drive down to the riverside town of Zhuoni.

I felt a certain excitement on arriving in the town. Choni! I was here! I immediately took a taxi from the simple courtyard bus station up the hill to see the Chanding monastery. Zhuoni was a busy little town with really just one main street running up from the Tao river. There were a few modern shops, restaurants and hotels by the riverside, but otherwise it was a quite unremarkable place. It didn't appear to be Tibetan, and most of the locals looked like Han Chinese or low key Hui Muslims.

About a kilometre up the hill we turned left into the the entrance of the monastery. As I walked through the main gate, I recognised the layout of the place from one of Rock's old photos, but the buildings were not the same. They had been rebuilt in a similar but not identical style. I started to wander about the buildings and take photographs, and it felt strange because there was hardly anyone about.

Apart from one or two Tibetan monks that I glimpsed walking about, I had the place to myself. The temples were all padlocked and there was nobody about to ask about having a look inside. I tried to catch the attention of one monk but he scurried off, unwilling to talk. I eventually found myself at the highest part of the complex, stood in front of one of the larger temples. It had started to drizzle with rain and it all felt like a bit of an anti-climax. A group of local people emerged from one of the outhouses and peered over my shoulder at the copies of the old Rock photographs of the place. The pictures barely rated a murmur, and when I asked one of the older men in the group about the pictures he just said "kanguo-le" - "We've seen them before."

I don't know what I'd expected to find at Choni, but this was quite underwhelming. I'd known that the original buildings would no longer be there - Rock himself had heard that the monastery had been almost completely destroyed after his departure by Muslim forces during the sectarian fighting of the late 1920s. According to Rock's biography, Prince Yang of Choni had abducted, raped and murdered some women related to the Muslim General Ma. In retaliation, the Muslim forces had ransacked Choni and slaughtered many of the locals. Prince Yang escaped the killings, but when he returned to take up residence at his yamen in 1928 he was set upon by his on servants and lynched in a nearby riverbed. Well, that was one version of his sticky end - I was to hear another version later in the day.

It was mid afternoon when I trudged back down the hill in the rain towards the town centre. I was hungry and was also anxious to find somewhere to rest up. After devouring a tray of steaming xiaolongbao in a hole-in-the-wall restaurant I walked into the modern town square - complete with massive video screen - and entered what I thought was the main hotel for Choni. It was a mistake. The stark interior appeared to be a deserted office complex. A man emerged from a side doorway and asked tersely what I wanted. When I said a room, he just gestured in that Chinese way with his lips and chin that this was next door. When I re-emerged into the daylight outside I read the sign and realised that I had just been trying to check in to the town's Communist Party Headquarters.

The hotel was actually next door, but I didn't even get chance to check in. At the reception I had just asked the female clerk for a room when I was approached by two young uniformed cops and a humourless-looking Chinese guy in a suit. One of the cops ostentatiously showed me his official badge in a leather wallet, and held it under my nose for my obvious perusal, as if to emphasise that there was no possibility that he might be an imposter. Then he uttered one word in English: "Passport." As the guy in the suit leafed through my passport, I was politely ushered to sit in one of the voluminous leather couches nearby. Without any prompting, I launched into Chinese, to make an explanation of what I was doing there.

I told them I was a tourist and that I had just come to visit the Choni monastery and take some photos because I had seen some pictures of how scenic it was in an old magazine. I took out the pictures of Rock to show them. The cops' stiff and formal attitude loosened a little when they heard me speak Chinese, and they gave me the almost reflex compliment for a putonghua-speaking laowai: "You speak Chinese so well". I babbled on, telling them that I was just here for the day and planning to leave the next day to go back to Lanzhou. "How did you get here?" they asked. When I said I had come on the bus from Xiahe, they frowned and corrected me - "You mean from Hezuo?". I said yes, and told them how I had swapped buses there. This did not compute, and I was told that "foreigners are not allowed to travel on the bus from Hezuo to Choni." I could only presume that the bus station in Hezuo had been instructed not to sell Choni bus tickets to foreigners, and that I had evaded this by jumping on the bus as it left town.

I made what I hoped sounded like a sincere and humble apology and promised that I would leave town as soon as possible. I showed them my return bus ticket that I had bought for the next day. Seeing all my camera gear, the older man in a suit asked if I was a journalist. I said no, and that I was a pharmacist - which was not untrue in that I had trained as one. He walked off with my passport and left me in an awkward silence with the two young cops.

I was feeling a bit nervous and my mind was racing through the possibilities of what might happen to me. Arrest? Put in a cell? A fine? Deported to Lanzhou? The one thing I really dreaded was having my rolls of film confiscated, and I cursed myself for not concealing them. I continued babbling on, trying to reassure them that I was just a regular tourist. I told them that I had just arrived in China from Australia and had already visited the big monastery at Xiahe, and therefore assumed there was no problem in coming to see the smaller monastery at Choni. One of the cops said that I was not able to visit Choni because it was ... he struggled a moment for the right word ... "sensitive". Speaking in an official tone he said that due to the current situation relating to minorities, it was not safe for me to be there.

The older cop returned with my passport, which he had photocopied, but he didn't give the passport back. He repeated the question about how I had got to Choni, and I repeated the answer I had already given. He then asked again whether I was a journalist, and I repeated that I was a pharmacist. He then pulled out what looked like an iPhone and tapped something on the screen. He showed it to me and it was a Google search on my name. The first entry was of the medical newsletter website that I worked for, and my title "Michael Woodhead - Editor". "Is this you?" he asked. I could hardly deny it - it had my photo there. I mumbled something about being a pharmacist who worked for a medical information service, but I could see they had already made up their minds. "Zou!" (Let's go!).

I didn't ask where we were going, but just accompanied them out of the building and along the street, one cop on either side of me. One of them solicitously insisted on carrying my backpack. I was taken into a courtyard next to the Party HQ and we entered an unmarked building that had a similar arrangement of corridors and apparently deserted offices. A police station? Or Party offices? Up the stairwell to the second floor, I was ushered into a room with a leather sofa, a coffee table and a couple of chairs. It could have been a doctor's waiting room. And there I was left to stay for the remainder of the day, with the two young cops for company. When I asked what was going on I was again told that "foreigners were not allowed in Choni" and my situation "was under consideration by the relevant authorities."

The older cop had disappeared with my passport again, and I was brought a cup of green tea and told to "rest a while". And there I "rested" for the remainder of the afternoon. After the initial shock of being detained had worn off, it was very tedious. Outside there was a constant hammering and crashing from a construction site, but otherwise there was nothing to do. I tried chatting to the two cops, but their thick local accents made it difficult for me to understand what they were saying. They were polite and friendly, but a little distant. To try break the ice a bit more, I told them a bit about myself and my family, how I was married and had two kids and we often visited China to see our Chinese relatives. In turn, they asked me what Sydney was like, and a few questions that revealed how little they knew about the outside world. Did we eat rice every day in Australia? Do they have many Chinese in Australia? And what kind of cars did the police drive in Australia?

All this time the door was always open, but it was quite obvious that I wasn't going anywhere. I tried to pass the time by pacing the room, looking out the window at the builders and then reading a bit of my Eric Newby book, Love and War in the Apennines (in which he had to work out how to pass many long hours in captivity). Late in the afternoon, I asked the cops if they were hungry. As if the thought had just occurred to them, they turned the question back on me - Was I hungry? Would I like to go out and eat something? When I said yes, they simply replied "OK - let's go ..." and we headed out and back downstairs. It was as if they were making it all up as they went along.

Not knowing how this would all pan out, and not wanting to push my luck, I suggested the first restaurant that I saw on the street outside, which inevitably was a Lanzhou beef noodle place. I went in and ordered the standard bowl of noodles from the Muslim chef-owner, but the cops didn't have anything. They just sat around as I ate, and said the same things that all Chinese do when around a foreigner eating. "Oh, you can use chopsticks! What do you think of our Chinese dishes? Nice? Can you stomach them?"

On our return to the 'waiting room' in the government building we were met at the door by the plain clothes cop. He returned my passport and just stated the obvious. "Tomorrow you are taking the bus to Lanzhou." I wasn't sure if this was a question or an order, so I just replied "Yes".

He then said vaguely that I could rest where we were and take the Lanzhou bus in the morning - it departed at 6am. One of the cops took me down the corridor to a smaller corner room that had a single bed with a bed roll, a chair and a table on which was a massive TV that seemed to take up half the room space. Down the corridor was a poky bathroom and squat toilet. Next door to me was a similar room with an earthy middle aged guy wearing a tatty suit in residence. He seemed to be the caretaker/doorman. His room also had a kettle and he spent most of the evening watching TV, smoking and cracking melon seeds. The two cops said they were going to leave me there, but first they would have to take my photo. I assumed they meant I would have a mugshot taken for their records, but instead they both pulled out their smartphones and took cheesy self-portraits of the three of us, instructing me to say "cheese" each time. One of them gave me the parting advice to "go to sleep early, you have an early start." The other added that I should drink more kaishui because I probably wasn't accustomed to the high altitude.

And so it was that I was apparently left to my own devices in the room. Was I still in detention or could I go out if I wished? I wasn't going to try find out. I turned on the TV and surfed the usual range of channels, but soon got bored of the Women's Channel, the Army Channel, the Kid's Channel and the Learn American-accented Chinglish channel. There seemed to be more ads than programmes. Then I decided to take the cops' advice and drink some water, but the flask in my room was empty. I went next door to ask the caretaker if he knew where I could get hot water and he jumped up to get me a filled flask from the several he had arrayed in the corner of his room - as if having a foreigner to live next door was the most normal thing in the world.

He asked the usual questions that I got asked all the time by Chinese when on the road in China. Where was I from? Was I here travelling? Was I alone? How long had I been in China?

I told him that I had come to see the monastery because I had been inspired by seeing pictures of it in the old days. He seemed puzzled as to why anybody would come all this way to see Choni monastery, and said that Labrang (Xiahe) monastery was "more fun" to visit. I told him that I had heard about the old Prince of Choni and that I had hoped to visit his old yamen or quarters. The caretaker then became quite animated and started telling me that there was now a memorial in town to the old Tusi. His old mansion had been turned into a primary school, he said, and there was a big memorial built there.

I told him how Joseph Rock has lived in the area for two years, but the caretaker had never heard about Rock and didn't seem interested. Instead, he said the "Choni Tusi" had become a hero of the Red Marchers because he had aided them when they had passed though the area in the 1930s. That made me stop and think - because this contradicted what Rock's biographer had said about the Prince of Choni being killed in 1928. The caretaker then recounted to me the story as if it had been told many times before, almost like an official history.

He said the Prince of Choni had been warned by his Chinese mentors in Lanzhou to be on the lookout for the arrival of the Red Army marchers in the early 1930s. The Chinese warlords in Lanzhou were affiliated with the Kuomintang (KMT) anti-communist Nationalists and wanted to prevent the Long Marchers moving north through a narrow defile called Lazikou near Choni. The Long Marchers had already won a victory by capturing the Luding Bridge from KMT forces in the now legendary battle that enabled them to cross the Dadu River and escape entrapment. The next barrier that Mao and his marchers faced after the Snowy Mountains was gaining access to the grasslands via Lazikou. According to the caretaker, the Choni Prince had been told to gather his local Tebbu Tibetan fighters and use them to help block the Lazikou gorge at a narrow bridge over a river. The steep-sided Lazikou gorge was a great obstacle and could easily be defended against thousands by just a few hundred armed men.

However, the Long Marchers such as Mao and his army chief Peng Dehuai had good intelligence about the Lazikou pass and its would-be defenders. They sent runners ahead with letters to the Choni Prince, saying that they were just passing through and would not occupy Choni or make any demands on the local people and their resources. The envoys stressed that the Long Marchers were an anti-Japanese force, and a friend of all the minority peoples.

Whether through patriotism or political calculation, the Choni Prince decided to defy his KMT sponsors and side with the Long Marchers and allow them passage through the Lazikou gorge. He instructed the Tebbu Tibetans to assist the Long Marchers and act as guides. The Red soldiers still faced a tough battle at Lazikou against KMT forces, but with the help of Choni Prince's guides they were able to outflank the defenders and make a breakthrough and eventually reach the Gansu grasslands and go beyond to establish their new revolutionary base in the loess caves of Yanan.

The general commanding the local KMT forces was humiliated by the defeat at Lazikou and would exact his revenge on the Prince of Choni for his treachery. According to the caretaker, several years later, after the Long Marchers had passed through and KMT control was re-asserted, the general returned to Choni and attacked the Prince's compound. The Choni Prince was captured and executed, but his son managed to escape.

When I asked what happened to the Prince of Choni's son, the caretaker said he became the new tusi until the Liberation, when his father, the late Prince, was declared a revolutionary martyr by none other than Zhou Enlai himself. Hence the local memorial. I found it grimly ironic that the Han Chinese authorities portray the non-violent Dalai Lama as an evil serpent, and condemn the 'old' Tibetan society as feudal and barbaric, citing examples of child sacrifices and serfdom. And yet here in Choni they put up memorials to the despotic local 'Prince' who had raped and murdered women and brutally taxed and oppressed the local people. I was later to see similar memorials to the savage Muslim leader General Ma Pufang in Xining. In China, political expediency can turn monsters into masters - and vice versa.

Interestingly, I also learned form the caretaker that the grandson of the Choni Prince had also grown up in the area, become a magistrate and was still alive and carrying on the family tradition, he added.

So it seemed that for once, the visit of Joseph Rock to an area and his acquaintance with local nobles was just a footnote in local history rather than a defining moment as it had been for his Shangri-La inspiring travels in Yunnan and Sichuan.

I retired to my room and tried to sleep, even though the construction hammers on the building site outside my window continued to clang until late into the night. I was worried that I would sleep in and miss the bus out of town but I needn't have worried. In the early hours I was woken by a young Tibetan woman night clerk who rapped on the door at 5am. I was ready to within a few minutes, but oddly found I had no escort. The young woman sleepily - and with a hint of sullen resentment at being woken so early - unlocked the thick bike padlock chain around the handles of the main glass doors of the building and released me like a bird into the cold dark morning of Choni.

I made my own way down the main street towards the bus station, humming to myself and wondering what would happen if I turned round and made a last visit to the monastery. Would anyone be watching to stop me? The streets were deserted except for a couple of old ladies sweeping up dust with those crude stick-and-branch Chinese sweeping brushes. I bade them a hearty "good morning" in English and strode across the bridge to the waiting bus. Already a few would be passengers were stood around the locked and darkened bus, stamping their feet and smoking in the nippy morning air.

They looked at me with curiosity and I smiled back stupidly, happy to be "out of jail". At five to six the driver strode up, opened the bus door and started the engine. I took my place on the half empty bus, which suddenly filled to capacity with babbling passengers who seemed to come out of nowhere at the very last minute. I looked out of the grimy window at Choni as the sky just started to lighten. A woman came down the aisle to check everyone's tickets, and then when I turned again to look out of the window, there was a tiny police van pulled up next to the bus with my two cop friends stood next to it. They didn't acknowledge me, but as the bus pulled out I looked back and saw them still stood there, watching my departure from Choni.

5 comments:

Michael this is incredible! So glad you survived the night :) What a story! You might need to change your name to Mike Woolhead at 6minutes...

Yes indeed - or change my 6minutes profile pic, or maybe wear a false beard while travelling?

太厉害了😂,因为马上准备去卓尼旅游所以到处搜Joseph Rock当年写的文章。文章没找到,发现了这篇博客,啥也没干读了一下午哈哈。谢谢你的分享,太有意思了!

Thank you for sharing!

I stumbled across your blog while doing some research on the 米拉日巴佛阁 in 合作市… There’s very little information available on the internet. I really wanted to know what the temple looked like before it was demolished during the Cultural Revolution… and I think the pic on your website is the ONLY example of the pre-revolutionary 佛阁 on the internet! Thank you so much for this. The trip you did was SO interesting – I love traveling around this area of China, having been to Hezuo myself. But there’s so much to discover, I wish I’d spent more time in Gannan!

Thanks Christian Jiang - As you can see from my latest post I have just been back to Hezuo as part of my cycling trip along the Yellow River - after 5000km of pedalling didn't realise when I passed through that it was the place I had visited a decade earlier!

Post a Comment