[Click here to go forward to Chapter 10]

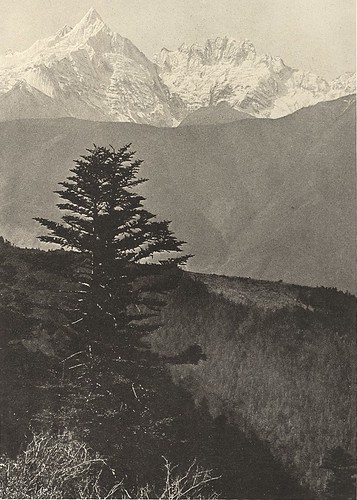

"Where in the world is to be found scenery comparable to that which awaits the explorer and photographer in north-western Yunnan?"

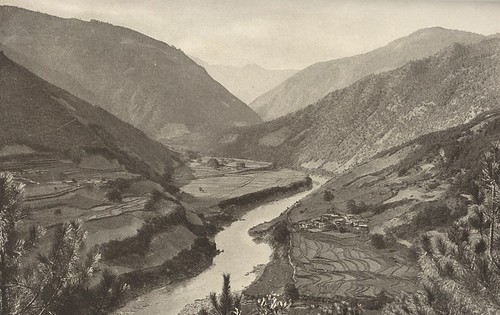

So wrote Joseph Rock in 1925 when he returned from an epic three month winter expedition to what he termed "the great river trenches of Asia". This is a unique area of northwest Yunnan, where four of Asia's major rivers run in parallel for a few hundred kilometres, creating huge canyons that are separated by high ridge lines of mountains.

In this corner of south-west China bordering Burma and Tibet, the Yangtze, Mekong, Salween and Irrawaddy flow close together from north to south, before diverging to follow their own paths across different countries and to empty into different oceans.

The easternmost river is the Yangtze - known as the Changjiang in China. After flowing south from its Tibetan headwaters, the river hits a mountain barrier and makes an abrupt turn northwards at Shigu, where it enters the Tiger Leaping Gorge. The Yangzte then almost immediately loops back down south, around Lijiang, before turning permanently eastwards to flow through the heart of China and ultimately to empty into the Pacific Ocean near Shanghai.

The Mekong - known in China as the Lancang Jiang - flows continuously south into Laos, Thailand then through Vietnam, where it finally enters the South China sea near Saigon.

The Salween, known in this region of China as the Nu River, or Nujiang, flows along the border between Yunnan and Burma for much of its length. The watershed to the west of the river marks the actual border between China and Burma, until the river eventually kinks westward into Burma and reaches the Indian Ocean at Moulmein.

For a short section in the north of Burma the Irrawaddy river also flows in parallel with these three major rivers.

The juxtaposition of these major rivers and canyons creates a dramatic transition from the tropical Burmese jungle to the temperate uplands of Yunnan and the alpine peaks and plateaus of Tibet. The sequence of three canyons and five high ridges acts as a barrier to the monsoon rains coming from the Indian subcontinent, and thus creates a series of unique micro-climatic areas, starting with the moist leech-infested jungles to the west of the Salween, and eventually reaching the arid highland areas to the east of the Yangtze, in the rain shadow of these huge peaks.

As well as having a wide variety of local climates, the region is also host to numerous different ethnic groups. To the north are the Tibetans, while to the west are the upland tribes of Burma, many of whom such as the Jingpaw and Lisu go under the umbrella term of 'Kachin' in Burma itself. Each of the river valleys has its own mix of minorities: the Naxi and Pumi in the Yangtze valley, the Lisu in the Mekong valley, and the Nu and the Drung in the Salween valley.

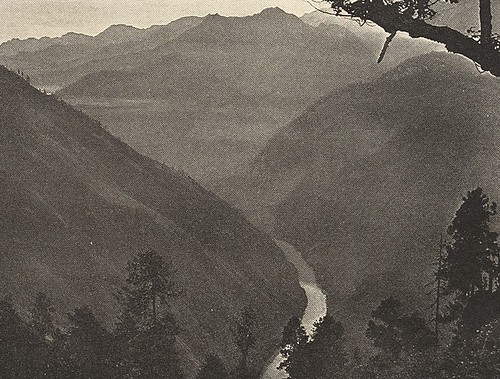

Rock's description of these river canyons as 'river trenches' is apt, for here are deep cuttings and gorges, separated by towering peaks of up to 25,000 feet high. These river-mountain divides of the Hengduan and Gaoligong mountains also form what became known as ‘The Hump’ in world war two, the great barrier that was surmounted by transport planes trying to deliver supplies to China from India after the Burma road was captured by Japanese forces.

In his article in the August 1926 issue of National Geographic, Joseph Rock once again opens by making dubious claims of being the first to really explore the region.

"Few have been privileged to climb the towering ranges separating the mightiest streams of Asia ...," he begins.

"No white man had previously had a glimpse of many of the scenes here photographed, for the few explorers who have penetrated these terrifying fastnesses have done so when the snow-crowned peaks were hidden from view by the enveloping monsoon clouds of summer."

What Rock fails to mention is that the region had already been visited and explored quite extensively by botanists such as Frank Kingdon Ward.

Kingdon Ward had tramped all over upper Burma, Yunnan and Tibet from 1910 onwards, and had chronicled his journeys in books such as Land of the Blue Poppy and Mystery Rivers of Tibet. Rock makes a brief mention of other explorers and botanists, such as Jacques Bacot and Heinrich Handel Mazetti, and describes how they had reached the Tiger Leaping Gorge (then known simply as the Yangtze canyons).

However, at the time of Rock's expedition to the 'Three Rivers' region there were also several Catholic churches in existence in the upper reaches of the Mekong and Salween rivers. These churches had been set up by French and Swiss priests in the late 19th and early 20th century, and the priests travelled extensively in the region and even built the first proper paths over the high divide between the Mekong and the Salween canyons.

So Joseph Rock was not the first to visit this region, but he says he aimed to be the first to photograph it and its people.

"Lured by the magnificence of the mountain rages and the weird and little known chasms in which these mighty rivers flow, as well as by the strange tribes living on the slopes of their gorges and in their valleys, early one October I left my headquarters in the little Nashi hamlet of Nguluko on the Likiang snow range, to explore and photograph."

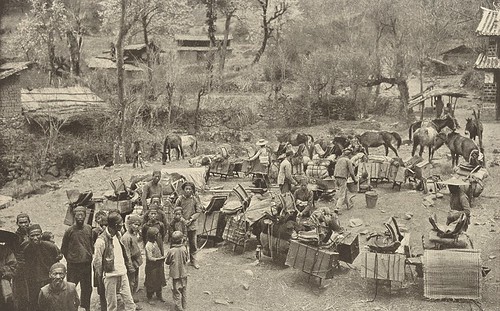

In October 1924, with the monsoon rains not yet over, Joseph Rock set out for his autumn and winter visit to the north west corner of Yunnan. As usual, he had a large retinue of Naxi servants, helpers and bodyguards, 15 men in all, plus numerous mules to carry his three month's worth of supplies.

When Joseph Rock set off from Lijiang, his aim was to walk up the Mekong (Lancang Jiang) river towards the French missionary post at Cizhong (then known as Tsechung) near Atuntze (now known as Deqin), and then cross the ridge over to the Salween by means of the Doker La pass, a traditional Tibetan pilgrimage route.

But first he had to first work his way around the Yangtze, which envelopes Lijiang in its first bend. Rock did this by passing through the village of Shigu, situated at the tip of the first bend of the Yangtze.

If you want to read more about this town and its history, I suggest you read Simon Winchester's book Yangtze, which tell you more than you need to know about why the river makes such a weird deviation at this point rather than continuing to flow south. Shigu was later a historic stopping off point for Mao's Long March.

But back to Joseph Rock - he describes his journey with the usual woes about flea-ridden rooms and ne'er-do-well opium-smoking Chinese. These grumbles are offset by his effusive words about the magnificent countryside he is passing though. I love his description of the scene from his balcony in the market town of Shigu, as his caravan seeks to settle in for the night. He describes it so well, you can imagine yourself right there. He is watching the scene as it rains and while "cats, dogs and dirty children add to the confusion":

"The lead mule with his large bell steps into the muddy courtyard, followed by his hungry co-sufferers. Without waiting to have their loads removed they fight their way to the troughs and try to eat through the baskets tied over their mouths. Dogs are stepped upon, pigs squeal, mules bray, while long dead ancestors are conjured up unprintable language by the exasperated muleteers. Everywhere mud, dung, cornstalks and odours which it would be difficult to analyse! Poor cook! In such surroundings he has to produce a palatable meal!"

On his way to cross the Yangtze-Mekong watershed, Rock passes the scene of a Nashi funeral, where grey-cloaked mourners prepared paper replicas of servants and furniture to be burned to accompany the deceased into the next world.

He then passed along a narrow track where spiders' webs were so thick as to need a stick to be held up in front of your face.

"Unless one held up a to separate the yellow threads and make a passageway through this labyrinth, one's head would soon have resembled a yellow ball of twine or fuzzy silk."

In this way, he plodded in five days up to Chutien, on the banks of a tributary of the Yangtze. This is the same route now followed by the road that carries bus and truck traffic from Lijiang (adjacent to the Yangtze) to Weixi (near the Mekong).

I made my own attempt to follow in Rock's footsteps along the Mekong in the early spring of 2002. It was to be a disappointing trip, marred by bad weather that prevented me from making the crossing of the Doker La from the Mekong to the Salween (Nujiang). Even in late March much of the Mekong valley was still gripped by dismal, winterish weather - rain in the valleys and snow higher up. With the high passes blocked, there was no chance of making the crossing, although I did not know this at the time I set off.

Initially, I tried to reach Deqin directly by bus from Lijiang. This meant stopping over in Zhongdian, the town that would later appropriate the name Shangri-La and re-invent itself as a tourist centre. In 2002, however, it was still a primitive and rather grim one street town, and the weather in March was bitterly cold, in contrast to the relatively mild climate in Lijiang. The cold weather and snow meant that the road from Zhongdian to Deqin via the high pass near Baima Shan mountain was closed. I would have to go back to Lijiang.

Ensconced in the friendly Tibetan Family Hotel, I pored over my maps in the cosy wooden common room and plotted an alternative route to the Mekong, via a smaller road from Lijiang that travelled a more direct route due east via a town called Weixi. This was closer to the route that Rock had followed from Lijiang. My maps attracted the attention of another traveller in the common room - a young woman from London called Shanti. When I explained my intentions to head up to the Mekong, she said it sounded interesting and asked if she could come along. So now I had a travelling companion.

Back in Lijiang we bought bus tickets to Weixi. Our bus left in the dark of early morning, and by midday had followed the route of the Yangzte to a town called Judian.

It was at 'Chutien', Rock encountered the first signs of Tibetan culture, a Buddhist temple in the town - the first or last outpost of Lamaism. He stayed in a loft from which opium smokers had been evicted and he marvelled at the clear country air at 9,000 feet, the stars overhead (there were holes in the ceiling) and the strange bunches of beans and white blocks of yeast stored in the room.

From here Rock crossed over to the Mekong via an pass called Litiping, which he described as undulating alpine meadows with hemlock, canebrake and rhododendrons growing in profusion, and birds singing. I must say that when we passed over the same spot on a bus from Lijiang, I found it to be not quite so enchanting - 80 years after Rock's visit, Litiping was a barren stunted grassland interspersed with sheep herders' rock shelters.

From this high point, Joseph Rock descended to Weixi, a small but substantial town where he paused to rest and restock his supplies, as well as develop some pictures. He said the town boasted a wall of mud, with a few dilapidated gates, and a post office where he was able - despite a lack of sufficient stamps - to post a letter to Washington DC.

In Weixi, Rock also spent a considerable amount of time providing medical care to the locals. However, he was dismissive of their blind faith in western medicine, and their expectation that just one dose of his pills would cure even end-stage tuberculosis. He also notes that the local cure for bleeding was cow dung.

My own experience of Weixi was of a very pleasant and rustic market town in the hills. Its cobbled streets and wooden houses gave it something of the atmosphere of the old Lijiang, without the throngs of tourists. Its hilly streets were given over to stalls selling all kinds of wares, especially herbal remedies. I saw a few brown-skinned Burmese traders selling oddments like Vietnamese toothpaste and some Indian-made joss sticks. It reminded me that the Burmese border was not so far away.

The other big thing on display in Weixi was orchids. Literally hundreds of them. In late spring when we visited, there were scores of people trading plant pots containing these strange flower plants. Apparently the more aesthetic samples were changing hands for hundreds of dollars in the belief that they confer good luck

The main thing about modern Weixi is that its character is predominantly Lisu. The Lisu we saw appeared to be very cheerful, industrious if a bit rough and ready, and in the higher reaches of the Mekong valley we found that many were Christian. Quite a few of the local villages had small churches, looking for all purposes like any other traditional Chinese building with the curved roof, but with a cross prominently displayed on the front.

Funnily, Rock did not seem to remark on this during his visit - perhaps at that time the work of the missionaries in the Mekong had yet to bear fruit. The great British proselytiser, J.O. Fraser, ('Fraser of Lisuland') was responsible for converting many of the Lisu to Christianity in the early 20th century, but his work only started around the Great War of 1914-18 and may not have had much impact on the Weixi area by the late 1920s.

Weixi is situated some way above the Mekong, and from here Rock descended to the village of Kakatang, where he observed that goitre was a major problem. One local man had such a large goitre that it weighed down his chin to the extent that he could not close his mouth. Needless to say, I saw no such evidence of iodine deficiency on my 21st century visit.

Rock continued on to the village of Petsinhsun - now know as Beixincun - where the headman wanted to have his photograph taken. Rock was amused to see him throwing on silk garments over his dirty clothes and then posing "as if he was the emperor of China".

Now Rock had finally reached the Mekong, but the route up the valley was primitive in the extreme.

"The trail was appalling and often the loads had to be removed from the packs and carried one at a time by the mulemen over the treacherously narrow spots high above the stream," he writes.

In 2002 there was a reasonably good road leading up the eastern side of the Lancang Jiang. Our bus was crammed with boisterous and diminuitive Lisu people and stopped every ten minutes or so at minor settlements, where they would load and offload their unusual cargoes. Many carried bushels of plants or twigs, while others hefted large plastic barrels filled with water in which swam live fish.

It took Rock seven days to travel up the Mekong as far as Cizhong, while we did it in a single day.

As he progressed further up the river valley, Rock noted that there were fewer Lisu and Naxi people and more Tibetans in evidence. And the Naxi who did live in the Mekong valley had adopted Tibetan ways and followed a Tibetan form of Buddhism.

Up through Kangpu to Yetche, Rock met a Naxi ‘king’ who he found to be friendly and dignified. Back in 1905, this local dignitary had saved the life a British botanist, George Forrest, who had been on the run from Tibetan lamas intent on killing him.

At that time, the Tibetans had greatly resented the presence of western missionaries in the Mekong valley, seeing their mission stations and churches as a springboard to convert all of Tibet to Christianity. The Tibetans' anger cumulated in the murder of all the western missionaries in the area around Atuntze [now known as Deqin], and their severed heads being put on display at the monastery there.

After this, pressure was exerted by western colonial powers on the Qing authorities in Yunnanfu (Kunming), and the western missionaries in north west Yunnan were given tacit support by the Han Chinese government, who wanted to destabilise and undermine the political power of the Tibetan lamas.

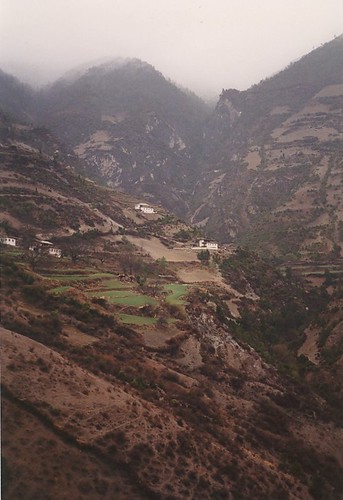

As he continued up the Mekong to the north, Rock noted that the scenery became grander as they proceeded northwards from the village of Yetche. He was now hemmed in by steep hills on both sides. And it is this narrowness of the valleys that has given the Mekong and Nu canyons their unique mode of transport - the cable crossings of rivers, like the flying fox. In other broader valleys these cable crossings would not be feasible. But Rock describes in great detail how he and the whole of his entourage - 15 men with all their horses and mules and supplies - were conveyed across the roaring river on rope slides.

He was intending to do this at Cizhong, but was persuaded to try a few miles further north as the Cizhong rope was past its use by date of three months!

The flying foxes are still in use along the Mekong, although these days they consist of steel cables, not twisted bamboo rope greased with butter.

Once across the river, Rock backtracked south to the mission station at Cizhong, where he met the French priest, Pere Jean-Baptiste Ouvrard, who had been working in this area for 14 years. Again, it is odd that Rock says almost nothing about Cizhong and its distinctive and remarkable Catholic church.

Perhaps he wanted to be the centre of the narrative and did not want to draw attention to the fact that others had been here well before him. Or perhaps it had something to do with his aversion to the Catholic church after his unhappy childhood experiences in Vienna of having the faith rammed down his throat by an overbearing and obsessively religious father.

Rock only mentions that the priest helped him recruit a further 13 Naxi, Lutzu and Tibetans to help on the next stage of his journey - the crossing of the Mekong-Salween divide.

When we arrived at Cizhong after a pleasant if somewhat erratic bus ride up the Mekong valley, we were dropped off at a small suspension bridge over the river. We crossed this and headed up over the crest of a hill to find the village of Cizhong clustered around a village square that doubled as a basketball court and outdoor waiting room for a primitive medical clinic operating out of a shack.

A few of the local Tibetan old folk were having glucose drips in their arm [to 'restore energy'] or undergoing acupuncture with massive needles embedded in their knees.

After a drink at the shack we were taken up the road by an old gent who turned out to be the caretaker for the Catholic church. I told him I was a Catholic as well, and he seemed delighted with this. I tried a few words of French on him, having read that some of the older villagers still spoke it, but he didn't respond to it. Instead, he took us up to the church at the top of the village and opened up the doors for us to have a look around.

It was quite a strange feeling to walk past a Buddhist stupa into the forecourt of a Gothic-style Catholic church in the middle of a mixed Tibetan and Naxi village in Yunnan. The church seemed old but well maintained - a bit like the caretaker himself.

We padded round the silent interior, peering at the statues of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, trying to translate the Chinese language Christian posters on the wall, and looking for the original decorations. On the ceiling were a beautiful arrangement of symbols that combined Eastern tradition with Christian meaning. Lotus flowers and swirly ying/yang symbols interspersed with stylised Roman crosses.

The altar was richly decorated with a pink floral cover, augmented by hangings of yellow silk and vases of local pink and red flowers. Above it, a statue of Jesus and the Latin inscription "Ecce Agnus Dei'.

The small bell tower was reached by some creaky wooden stairs, and gave views over the collection of several hundred houses that made up Cizhong. The traditional Chinese/Tibetan-style of the village houses was offset by the satellite TV dishes that most of the houses had on their flat roofs.

We spent an awkwardly reverential half hour padding around the dark interior, gazing at the decorations and I made what I thought was a generous contribution to the collection box. But my deferential sense of awe was punctured slightly when immediately after this the caretaker demanded an additional 20 kuai each for letting us have a look round!

We stayed the night at Cizhong in the house of a local teacher, Mr Lee, who lived right next to the church and looked after its vineyard. The vines had been planted by the last French priests to live in Cizhong, and still produced a drinkable sort of red wine, which he served us that evening from a plastic petrol can. The type of grape was now unique to Yunnan, he told us, as it was an old and unproductive strain no longer used by the French wine industry. till, it was enough to produce 100 litres of wine a year in Cizhong.

Over a dinner of sinewy chicken in a globby yellow soup, Teacher Lee told us a bit about the village. It was half Tibetan and half Naxi, he said. A bit like his own family - he was Naxi and his wife a Tibetan. And despite being an overseer of the Catholic church he himself was a Buddhist, as witnessed by the large mural of the Potala palace and the pictures of the Dalai lama over his fireplace. A collage of family photographs on his wall also showed his own travels to Tibet.

Mr Lee told us that the village was a harmonious place, where Christians and Buddhists had lived together peacefully for centuries. He said about 80% of the villagers were nominally Christian, but there was no longer a priest in the village - only a visiting cleric who tended to many of the small churches in the Mekong valley. Mr Lee said the younger people in the village were not so interested in Christianity - they were more interested in going to the bigger cities for karaoke, to buy clothes and mobile phones. Materialism rather than Marxism was the biggest threat to the church, it seemed.

We saw his own house was neat and pleasant - with sturdy wood fittings common to most Tibetan houses in the region. Downstairs in the yard there were pigs, cows and chickens. Upstairs on the flat roof where corn was stored, there were more rooms where we stayed the night - in his son's study room, complete with a desktop computer.

It was only later that I learned a little more about the history of Cizhong and its unique Christian faith.

It seems that French missionaries established a church here in the late 19th century after their initial efforts further north in Tibet were thwarted by aggressive opposition from then powerful Tibetan lamas. Their first churches were burnt down and many of the missionaries were killed by local outlaws with the blessing of the Tibetan lamas. Cizhong was then chosen as a spot to build a church because despite its predominantly Tibetan populace it lay outside the border of Tibet - and the influence of the lamas. Under haphazard Chinese authority, the missionaries built their church and tried to set an example in the ways of the Lord to their Tibetan flock.

It obviously worked, and many local Tibetans and Naxi were converted. However, under the unstable Chinese warlord regimes the north west of Yunnan was never a safe place - and the missionaries were still plagued by bandits and lawlessness. In 1905 the Tibetan lamas tried to drive them all out of the Mekong valley and after killing two priests, succeeded in doing so, for while.

Swiss missionaries from the Order of St Bernard took over from the French. The last western priest at Cizhong was Father Alphonse Savioz, who was there from 1948 to 1951 when he was driven out by the newly installed Communist authorities. He now lives in Taiwan. One of his colleagues, Fr Maurice Tornay was not so fortunate. As parish priest at the Tibetan village of Yakarlo to the north, he was in conflict with the Tibetan lamas even into the 1940s. He made arrangements to go to Lhasa to negotiate a ‘truce’, but was murdered by his Tibetan enemies soon after he set off. He was declared a saint by Pope John Paul several years ago.

And so, despite it appearance as a tranquil ‘Shangri La’ of Christianity in the wilds of Yunnan, Cizhong has a turbulent and unhappy past and an uncertain future. It is slowly becoming known as a tourist spot, and it may not be long before coach loads of tourists clog up the dusty lanes of this village. Already a Kunming company has started to develop a ‘Cizhong wine’, allegedly based on the grape variety originally introduced by the French priests.

From Cizhong, Joseph Rock crossed over the 15,000 foot high mountains to the Salween (Nujiang) in the west via the (Sila) Se La pass, and spent two weeks exploring its settlements and monasteries. I will describe my own travels to the Salween (Nujiang) in a later chapter.

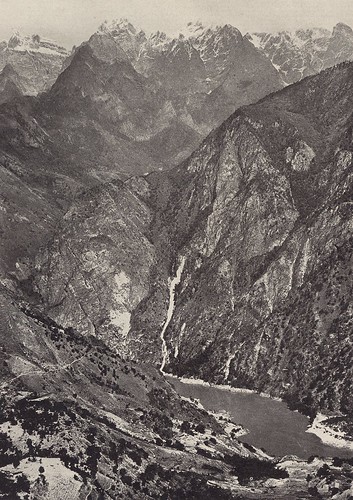

Leaving most of his supplies behind at Cizhong, Rock ascended first from the Mekong river up a steep zig-zagging track through oak and pine forests to a ridge about 11,000 feet up. From here he had great views of the Baimashan mountains south of Deqin. Continuing up to the bleak pass, Rock passed through deciduous forests of maples, with wild cherries and rhododendrons growing in the bush. We, however, were told quite categorically by Teacher Lee in Cizhong that the pass over the Se La was closed by deep snow. We attempted a recce and spent half a day ascending high above the river behind Cizhong, gaining great views up the Mekong valley and of the mountain to the north.

There were no other houses or settlements higher up in the mountains, but some of the herders we encountered up there also emphatic that the mountain crossing over to the Salween were closed. Reluctantly, we headed back down to Cizhong.

The next day we continued our journey up the Mekong, but this time on foot. We walked up the dusty road alongside the river to Yanmen (Swallow's Gate), where we stayed for a night. The Tibetan and Naxi people we met along the way were friendly - almost everyone urging us to rest and to come into their homes to have something to eat. Maize seemed to be the local crop - and the corn was spread out on the road to remove the husks.

In one small settlement we heard a strange thumping and groaning noise. When we went into the house to investigate we found three young Tibetan monks sat upstairs performing a house blessing ceremony. They banged on drums, blew on horns, rang bells and chanted unceasingly, unfazed by the appearance of two foreigners as spectators.

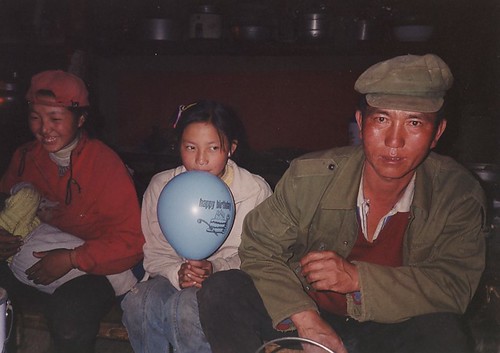

Tired from our day of walking, we rested in the house for a while and shared some noodles with the friendly hospitable Tibetan residents. In some ways, they looked very similar to the Mekong Tibetans photographed by Joseph Rock.

They passed the time printing prayer colourful flags and making butter sculptures, which they put up around their house temple.

Beyond Yanmen we passed a narrow gap in the steep sided gorge, from which a mountain river emerged. I presumed this to be the outlet of the notorious Londjre gorge that Joseph Rock climbed down on his return to the Mekong from the Salween.

"Of all the trails along which we had passed thus far, none could compare with that which leads from Londjre gorge out into the Mekong. It is a veritable corkscrew up a weird black chasm, at the bottom of which roars the stream coming from the sacred Dokerla. The trail is built against a rocky wall of sandstone in short, steep zigzags, a most appalling structure of tree trunks suspended over the deep, narrow, yawning black canyon with overhanging cliffs. A gale was blowing in addition, which meant that at every turn one had to brace oneself against the wind, holding tightly to the cliff."

As we continued up the river the valley narrowed - in some sections the river ran swiftly between dramatic high walls of rock.

We wanted to have another try at crossing over to the Salween, and we thought the Doker La pass might be open even when the Se La was closed by snow.

The Doker La is a major pilgrimage route for Tibetans. It marks the official cultural border between China and Tibet, and according to Rock, it saw thousands of Tibetan pilgrims crossing it every year.

"A constant stream of pilgrims treads the narrow trail with the sacred prayer Om Mane Padme Hum ever on their lips as they whirl prayer wheels in teir right hands. Thus they acquire merit. Many commit suicide by throwing themselves down the Dokerla, for to die on that sacred spot means emancipation and deliverance from re-birth. Some there are, especially nuns and monks, who do nothing all the year long but cross the Dokerla in penance."

To reach the Doker La we no longer needed to use the rope bridge that was the only way of crossing the Mekong when Rock visited. Now there was a primitive bridge, across which mules were plodding, and which seemed to sway in the strong wind blowing up the Mekong gorge.

We ascended for hour after hour along a simple trail, but it became increasingly evident that the Doker La was closed. The weather worsened as we got higher, and everyone we met along the way told us there was no way across. In this part of the Mekong there were quite a few small Tibetan houses dotted on the higher slopes, and it was to one of these that we turned for accommodation in the late afternoon.

The mountain ridge ahead of us was socked in with cloud, and it was starting to rain more heavily. When a rough looking Tibetan farmer herding some goats asked us where we were going, we told him about our abortive plan to cross the Doker La. He shook his head and said the trail was not usually open until late May - sometimes June. He was then kind enough to invite us to spend the night at his place.

And so it was that we spent the night sleeping on the floor of his threadbare wooden house house, at an altitude of around 12,000 feet above the Tibetan hamlet of Yongjiu on the Mekong. In the gloomy interior we juggled with walnuts and watched a Hong Kong kung fu movie on his dated TV. The farmer was only in his 40s but was already a grandfather - his teenage daughter was nursing a baby, breastfeeding the little mite while piglets and kittens and puppies played underfoot.

The next morning we woke up stiff and cold, but our decision not to continue on to the Doker la was vindicated - it was pouring with rain. We said a big thank you to the farmer and headed back down to the river. The route that had taken us several hours to climb up now took only an hour in descent.

At the windy bridge we managed to find a shack to eat noodles, and we took a minibus along the last part of the route up to Deqin. It was a scary ride, along a narrow road that rose higher and higher above the river, and which had precipitous drop offs and some very scary tight corners.

Deqin was a scrappy town of ugly Chinese concrete buildings, wedged in the mountains. In Rock's time it was known as Atuntze, and it comprised just a few stone and mud buildings and a small market place ("where people from the northern steppes bartered merchandise with the Chinese").

Rock says little about it in his article except that it was still "essentially a Tibetan town", despite being annexed by the Chinese into Yunnan in 1703.

Fei Lai Si

It was at the Fei Lai Si monastery just outside Deqin that we got a glimpse of the "peerless peak" of Miyetzimu (Meili) that Rock described so rapturously as "the most glorious peak my eyes were ever privileged to see. No wonder Tibetans stand in awe and worship it. It is like a castle of a dream, an ice palace of a fairy tale, or an enormous mausoleum with gigantic steps and buttresses all crowned by a majestic dome of ice tapering into an ethereal spire merging into a pale blue sky."

Even in 2002 the viewing area for the mountain had become a tourist trap, with hawkers selling joss sticks and other offerings to be made at one of the many shrines.

The tourist route also included a visit to the Minyong glacier that lies beneath Meili Xue Shan. Instead, we opted to travel the same route back down into the depths of the Mekong canyon, but turned left at the river to visit the hamlet of Yubeng. At the junction of the road near the Mekongwas we stopped at a small Buddhist chapel, called the 'Jungle Temple'. Inside, there were effigies of Buddhist deities, but also evidence to confirm Rock's observation that the local people also worship the mountain itself as a deity.

The route to Yubeng then branched off south along the western side of the Mekong. Once again the road was a nightmare for the squeamish and those with a fear of heights, as it ran along the sides of a precipitous sided canyon, high above the river.

Mekong, 1924

We stayed at some hot springs near Xidang before walking over to this Tibetan mountain village of lower Yubeng, where we spent a frustrating few days waiting in vain for the weather to clear.

It rained almost constantly and there was nothing to do except site inside and wait. On the rare occasions when the rain stopped, we played the locals at snooker on a wonky outdoor table.

Huddled round a fire in a bucket that gave off almost no heat, we had plenty of time to reflect on what we had seen so far - and what we were missing. We tried hiking through the deep snow to see the sacred waterfall and the 'magic lake' but it was hard going, and after hours and hours of walking we saw very little. The permanent fog also meant we could see almost nothing of the mountains from Yubeng. This was no Shangri La.

We spent a final night in Xidang at the Tibetan 'disco' being held in the main hall, just under our guesthouse room. Young Tibetan lads vied with each other to show who was the most macho on the sidelines of the dance floor. A few fights broke out and the music blared on until well past 3am.

Unable to sleep, I made the foolish mistake of walking out of the guesthouse at 3.30am, thinking I could walk down the road and start hitch hiking early when I reached the main road by the river. I had forgotten that Tibetans turn their dogs out at night to guard their properties, and spent the rest of the night huddled in the remains of a wooden shack, clutching my backpack in front of me and trying not to attract the attention of roaming dogs. It was an inauspicious end to my trip, one that was quite at odds with the Joseph Rock hyperbole.

2 comments:

Just got back from Feilaisi and Yubeng. We were lucky to have clearer weather than you did, but Feilaisi is heading for even more development. So it's easier to get a room there, but "Rustic charm" will not feature in future descriptions.

Nice, thorough piece, as usual.

Regards from Hong Kong

I visited Lijiang recently and bought the book by Peter Goullart at the Dong-Ba Museum. I saw the work of Rock displayed in the Museum. Very impressive. Thanks for posting your study of him on the web.

Post a Comment