[Click here to go forward to Chapter 4]

When Joseph Rock arrived in Yunnan on a plant-hunting trip from Siam (Thailand) in 1922, the province was in a sorry state of anarchy. Like other southern provinces of China, it had slipped out of the control of Peking and was ruled by a succession of corrupt local Chinese warlords. These figures, who styled themselves as scholars and nobles, were little more than leaders of an armies of gangsters, with opium as their main source of revenue.

Their rule was centred on self-enrichment from the province, not actual government of the province. Tang Chiyao, for example, was nominally governor of Yunnan in 1922. He had disposed of his predecessor – a relatively decent man - by execution and he allowed his soldiers to roam the province like official highwaymen, ransacking the mule caravans and extorting taxes from wherever they could. He presided over a province whose main agricultural crop was the opium poppy, the revenue from which Tang derived most of his power.

Tang’s reign would last until 1927, when he was overthrown and executed by a more politically astute rival, Long Yun. As nominal head of Yunnan province, Long Yun paid lip service to the rule of the Kuomintang (KMT) and its leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek in distant Nanjing. Long even made some moves to contain the worst of the rampant banditry and anarchy. In this way, Long Yun managed to retain a grip on power in Yunnan into the Second World War.

At a more local level, Joseph Rock would have encountered the minor officials and magistrates of rural Yunnan, who owed their positions to the tributes they paid in opium and silver to the provincial governor and his cronies. Lower down the scale were the merchants and tradesmen, with the peasant farmers and coolies at the very bottom of the social ladder.

As a westerner, Rock would have enjoyed the privilege of extra-territoriality that made him effectively above the laws of China. In the 1920s, there were few foreigners in Yunnan, and those that did find themselves in trouble would expect their consulates in Kunming to have leverage over the Chinese authorities.

At that time, Han Chinese rule and influence did not extend as widely as it does see today. Yunnan province was home to many non-Chinese ethnic groups such as the Lolo (Yi), the Naxi of Lijiang and the Bai or Minchia of Dali, who existed in varying degrees of independence from or assimilation with the Han Chinese. There was also another recent migrant minority - the handful of western missionaries who had set up churches, schools and clinics in far flung communities.

At that time, Han Chinese rule and influence did not extend as widely as it does see today. Yunnan province was home to many non-Chinese ethnic groups such as the Lolo (Yi), the Naxi of Lijiang and the Bai or Minchia of Dali, who existed in varying degrees of independence from or assimilation with the Han Chinese. There was also another recent migrant minority - the handful of western missionaries who had set up churches, schools and clinics in far flung communities.Yunnan also had a significant Muslim population, which had risen up against the Qing Manchu rulers in the late 19th century and conquered towns such as Dali. When French explorers trying to find the source of the Mekong passed through ‘Tali’ in the 1860s, they found the town was the centre of an independent Islamic mini-state, presided over by a Sultan.

This Muslim uprising was later put down with great ruthlessness by Qing troops, who razed whole districts to the ground without mercy. The entire Muslim population of Dali, for example, were slaughtered in 1873 after the town was besieged by Qing troops at the behest of the governor Cen Yuying. He promised to treat the inhabitants leniently if they surrendered, but when the Muslim leader gave himself up, the warlord went back on his word. No Muslim was spared, and the nearby Erhai Lake was reputed to have been full of corpses of women and children who tried to flee.

This Muslim uprising was later put down with great ruthlessness by Qing troops, who razed whole districts to the ground without mercy. The entire Muslim population of Dali, for example, were slaughtered in 1873 after the town was besieged by Qing troops at the behest of the governor Cen Yuying. He promised to treat the inhabitants leniently if they surrendered, but when the Muslim leader gave himself up, the warlord went back on his word. No Muslim was spared, and the nearby Erhai Lake was reputed to have been full of corpses of women and children who tried to flee.The capital of Yunnan, Kunming, was then known as Yunnan-fu. It was a backward provincial town, with few amenities, and yet it had a significant foreign presence in the form of French, British and American consulates, due to its proximity to Indo-China and British Burma. Eighty years ago, Kunming had better transport connections to Hanoi and Mandalay than it did to Peking.

Rock used Kunming as his base, and would often journey to the city from his remote locations in the Yunnan hinterland. It was also one of the last places that he stayed ever in China, before he was deported in 1949.

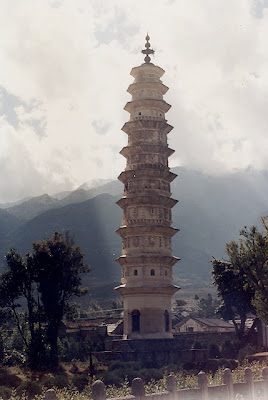

Dali pagodas photographed by Joseph Rock, 1920s.

Dali pagodas photographed by Joseph Rock, 1920s. Dali Pagodas in 1990

Dali Pagodas in 1990My first visit to Yunnan, 1990

I arrived in the modern city of Kunming in early November of 1990, after a 30-hour ‘hard sleeper’ train ride from Guilin. It really had been a ‘hard’ journey, and I’d become so sick of the staring, the spitting and the chain smoking of my fellow passengers that I spent much of the train trip sequestered on my top bunk, trying to keep out of their way.

Arriving at 5am, we were turfed off the train into the bitterly cold pre-dawn darkness. I sheltered in a café on the station forecourt for an hour, until it got light. I then made an abortive attempt to take a minibus into the city centre, but ended up boarding a tourist coach by mistake. When it started heading out of town, all my gesturing and attempts at speaking Chinese to get the driver to stop were ignored. It was only when I got up and started shouting and trying to wrestle the doors open that he pulled up. The other passengers were all snickering and muttering about the ‘crazy foreigner’ as I dragged my bag off the bus, cursing the driver and cursing China.

I eventually managed to flag down a taxi, and the driver was able to comprehend me enough to take me to the Camellia Hotel, one of the few places in Kunming that was officially open to oreign tourists. The Camellia was a shabby, Soviet-style institution, with dim cold corridors guarded by a female 'key keeper' on each floor. On my floor, the young woman concierge sat rugged up behind a shonky podium, tapping out a tune with one finger on an electric organ. She rose reluctantly and sullenly to open the door to my dorm room.

I eventually managed to flag down a taxi, and the driver was able to comprehend me enough to take me to the Camellia Hotel, one of the few places in Kunming that was officially open to oreign tourists. The Camellia was a shabby, Soviet-style institution, with dim cold corridors guarded by a female 'key keeper' on each floor. On my floor, the young woman concierge sat rugged up behind a shonky podium, tapping out a tune with one finger on an electric organ. She rose reluctantly and sullenly to open the door to my dorm room.After I dumped my gear and went for a walk about the city I had to wonder why Kunming had received such a good write up as the beautiful ‘Spring City’ in my guidebook. After the exotic peaks and sub-tropical foliage of Guilin, Kunming seemed to be a grey, soul-less city of the kind that I had always expected to encounter in Communist China. There was little colour: the people of Kunming wore Mao suits of dark blue or green, or shabby western-style black suits with white shirts. The architecture was mostly grim concrete blockhouse style, although there was an ‘old town’ cinsisting of poorly maintained rickety three-storey terraces. The shops were pokey and drab, and even the Vietnamese coffee shop that was mentioned as a highlight in my guidebook seemed to be no different to all the other grubby hole-in the wall noodle shops. It sold bitter coffee poured from a metal jug and bread rolls that were hard enough to break your teeth. I ended up having lunch at a ‘Soldier-Worker-Peasant’ canteen that sold cheap dumplings.

In the afternoon I tracked down the long-distance bus station and pushed my way through the chaotic hordes gathered around the ticket window to ask about travel to Dali . The only option available was an overnight 'sleeper bus'. So be it. Anything to get away from Kunming.

In Rock's time, Dali was ruled by a thuggish psychopath called Chang Chieh-pa or 'Chang the Stammerer'. Chang was one of the local ‘Minchia’ (Dai) people, a former muleteer who had turned to banditry. He boasted of having murdered 300 people and of his practice of eating human hearts. Chang led a band of around 5000 bandits in the Dali area, keeping them in line by forbidding opium and punishing them with cruel practices such as cutting off the lips of liars. Rather than confront this local strong man, the provincial governor had bought him off by appointing him a 'general' and sub-governor of Dali district. Despite this official appointment, Chang continued his habitual plundering of trade caravans and travellers passing though the Dali area, which was three days from Yunnan-fu.

It's hard to believe now, in the days of freeways and luxury coaches that can whisk you from Kunming to Dali in just a few hours, that the road journey to Dali used to involve two days of purgatory. In 1990 the ‘highway’ to Dali was a potholed country road and on this route I took the overnight sleeper bus to what I was led to believe would be China's answer to the Swiss Alps. Even with a 'bed' seat, earplugs and an eye mask I got no sleep whatsoever as the bus jolted over a road that seemed to be 95% roadworks, while the driver kept us awake with his constant blaring on the horn. Just when I thought that I might actually nod off, at 1.30am the bus lurched to a halt for a rest stop at a roadside noodle stall. So it was not surprising that my first impressions of Dali were coloured by my crankiness from lack of sleep. At 7.30am in the morning in November, Dali was freezing and still dark. I was not a happy traveller.

It's hard to believe now, in the days of freeways and luxury coaches that can whisk you from Kunming to Dali in just a few hours, that the road journey to Dali used to involve two days of purgatory. In 1990 the ‘highway’ to Dali was a potholed country road and on this route I took the overnight sleeper bus to what I was led to believe would be China's answer to the Swiss Alps. Even with a 'bed' seat, earplugs and an eye mask I got no sleep whatsoever as the bus jolted over a road that seemed to be 95% roadworks, while the driver kept us awake with his constant blaring on the horn. Just when I thought that I might actually nod off, at 1.30am the bus lurched to a halt for a rest stop at a roadside noodle stall. So it was not surprising that my first impressions of Dali were coloured by my crankiness from lack of sleep. At 7.30am in the morning in November, Dali was freezing and still dark. I was not a happy traveller. Things picked up once I had negotiated myself a room at the only hotel in town open to foreigners - the Dali Number Two Hotel. This undistinguished concrete pile was ridiculously cheap at seven yuan for a dorm bed. Once installed, I found a cosy café nearby that was obviously targeted at westerners: Jim's Peace Café. Jim was a laidback Chinese guy who spoke a kind of California hippy version of English. Maybe he’d been partaking of the marijuana that grows freely around Dali, but Jim certainly had the mannerisms of the stoner. I wasn't complaining. He ran a nice café, in fact pretty much the only café in town, that catered to my squeamish western tastes. I didn't want to eat rice gruel or beef noodle soup for breakfast, and Jim’s offered toast, muesli, banana pancakes and even coffee made from locally-grown Yunnan beans.

Things picked up once I had negotiated myself a room at the only hotel in town open to foreigners - the Dali Number Two Hotel. This undistinguished concrete pile was ridiculously cheap at seven yuan for a dorm bed. Once installed, I found a cosy café nearby that was obviously targeted at westerners: Jim's Peace Café. Jim was a laidback Chinese guy who spoke a kind of California hippy version of English. Maybe he’d been partaking of the marijuana that grows freely around Dali, but Jim certainly had the mannerisms of the stoner. I wasn't complaining. He ran a nice café, in fact pretty much the only café in town, that catered to my squeamish western tastes. I didn't want to eat rice gruel or beef noodle soup for breakfast, and Jim’s offered toast, muesli, banana pancakes and even coffee made from locally-grown Yunnan beans. As I began to feel more like a human again I walked the streets of Dali, and began to appreciate its charms. It was still essentially a small walled town, and I could understand how its traditional buildings, the lake and the beautiful mountain surroundings could lure travellers for extended stays. The sun rose and bathed the long ridgeline of the Cangshan mountains to the west in a golden glow. There appeared to be a dusting of snow along the higher peaks. The fabric of the ancient Bai town was still intact - the wooden framed stone buildings were evidence of Dali's reputation as a centre for builders and masons. The narrow cobbled streets echoed to the sound of hawkers and traders, and the brown-skinned Bai themselves seemed a tough but friendly people.

Most of the men wore the same utilitarian blue or green Mao suits that were still standard work wear in China, but many of the Bai women dressed in their traditional blue capes and had colourful turbans fashioned out of what looked like tea towels.

Most of the men wore the same utilitarian blue or green Mao suits that were still standard work wear in China, but many of the Bai women dressed in their traditional blue capes and had colourful turbans fashioned out of what looked like tea towels.Although he wrote extensively about the Naxi people and their culture, Rock said almost nothing about their close neighbours, the Bai. For that, we have to turn to Rock’s contemporary and fellow Lijiang resident Peter Goullart. In his book Forgotten Kingdom, Goullart admits that he had little liking for Dali or its inhabitants. He felt the town still had a gloomy atmosphere of death about it, and he found the Bai (or Minkia as he called them) to be rather stingy and calculating compared to his Naxi and Tibetan acquaintances in Lijiang. The Bai women, Goullart thought, were money grabbing, and would hire themselves out as porters to carry excessively heavy loads simply because they were paid by weight.

The Bai people’s gifts always had strings attached, said Goullart, and they never returned the compliment of an invitation to lunch or dinner.

Nevertheless, he could not help but admire their ‘uncanny’ skill in carpentry and masonry.

“Even the meanest house must have its door and windows beautifully carved and its patio adorned with exquisite stone figures and vases arranged with striking effect,” he wrote.

The Bai people were the craftsman of Yunnan – they built the grand houses of Yunnan and were commissioned by every minor chief and potentate to do the masonry and woodwork of their palaces, houses and temples. At the western end of town, as I walked up to view Dali’s famous landmark – a trio of nine century pagodas - I passed modern Bai craftsmen cutting slabs of marble with primitive power driven saws driven by a belt from the two stroke engine of the ubiquitous tuolaji tractor. Bai women were hauling cabbages from the fields into wicker baskets on their backs, which they ferried to a waiting truck already piled high with the vegetable.

My gaze kept going back to the mountains, and as a compulsive hillwalker I searched out a likely walkable route to the highest summit, on top of which I could just make out a small building with an antenna. I decided to try tackle it the following day, and retired back to Jim's café for a beefsteak and chips, a ‘cold remedy tea’ and an early night.

Climbing the Cangshan Mountains

I was woken early the next morning by two contradictory sounds: one was the scratchy Chinese erhu music being played through public loudspeakers and accompanied by a solicitous female Chinese voice that sounded to my uncomprehending ear like it was encouraging the whole town to wake up and face the day with a good socialist spirit. The other sound was that of a fellow resident at the Number Two Hotel who was making repeated and very audible attempts at clearing his throat and expelling the contents in a very echo-ey concrete communal bathroom.

This seemed to sum up the constant dichotomy of China: a land of ancient culture, ritual manners and dainty music, which simultaneously offered up revolting habits such as spitting, shoving and pissing in the street. Was it just a communist thing, I wondered?

After breakfast I bought a few snacks and hiked across the main road and out of the old town. I passed the three pagodas again and followed a cobbled road past some vegetable fields, twisting through another small village, until the road petered out into a dirt track that ran up into the pine woods> Then the serious uphill hike started.

It was a relatively peaceful walk up through the trees, but I could still hear the sounds of truck horns, quarry blasting and some sort of factory machinery in the distance. After about half an hor of climbing, I arrived, knackered, at the Zhonghesi temple, which was a beautiful serene spot with great views over the town and the Lake Erhai beyond it. The square shape of old Dali town and its grid like street pattern was now evident.

At the temple a friendly group of walnut-brown men were sitting about, and they were dressed in a mixture of army and civilian clothes. Using hand gestures, they invited me to sit down with them, and they made me drink some bitter-tasting green tea from a cracked flowery enamel mug. I couldn't work out how they were able to drink it without swallowing the big tea leaves and stalks that floated on top. Using my phrasebook they explained that they were local police - gonganju - and that they were up here looking for two porters who had failed to return from a ferrying trip up to the TV station two days ago, presumed lost in a snowstorm. The cops then rose to leave, taking a basket full of pine cones and a primitive-looking single bore rifle with them.

At the temple a friendly group of walnut-brown men were sitting about, and they were dressed in a mixture of army and civilian clothes. Using hand gestures, they invited me to sit down with them, and they made me drink some bitter-tasting green tea from a cracked flowery enamel mug. I couldn't work out how they were able to drink it without swallowing the big tea leaves and stalks that floated on top. Using my phrasebook they explained that they were local police - gonganju - and that they were up here looking for two porters who had failed to return from a ferrying trip up to the TV station two days ago, presumed lost in a snowstorm. The cops then rose to leave, taking a basket full of pine cones and a primitive-looking single bore rifle with them.I set off to carry on up the track through more forest, but not before a woman attendant at the temple tried to warn me about something up there. The track was well worn and became quite steep, emerging into clearing and the winding up around the edges of rocky outcrops, with the occasional grand lookout. I plodded on upwards, and it just seemed to go on forever. I started to feel the effects of altitude - it must have been between 8,000 and 10,000 feet up and I was taking longer to recover on my regular pauses to get my breath back. It became chillier and damp, and the going became harder as the grass covering parts of the track was slippy. I didn't feel too isolated, though, because below me I could still see the town and also hear local people working nearby in the hills whistling and calling to each other.

I continued plodding on upwards relentlessly, for an hour and another hour, occasionally getting a good vantage point, but never seeming to be getting any nearer to the elusive TV station at the summit. It still looked as distant as ever.

I continued plodding on upwards relentlessly, for an hour and another hour, occasionally getting a good vantage point, but never seeming to be getting any nearer to the elusive TV station at the summit. It still looked as distant as ever. By mid-afternoon I had climbed well above the tree-line and started to get worried about the time. The sun was moving behind the mountain ridge and soon I would be in shadow and unable to feel its meagre warmth. I set myself a 'turnaround' time of 3pm and plodded on. The scenery was superb. The grey rock outcrops had that strange jagged appearance that I had seen in Chinese ornamental gardens - but here writ in large scale. There were occasional fir or spruce trees breaking the skyline and what appeared to be rhododendron bushes. The sky was clear and the air was sharp - and I was losing my stamina.

By mid-afternoon I had climbed well above the tree-line and started to get worried about the time. The sun was moving behind the mountain ridge and soon I would be in shadow and unable to feel its meagre warmth. I set myself a 'turnaround' time of 3pm and plodded on. The scenery was superb. The grey rock outcrops had that strange jagged appearance that I had seen in Chinese ornamental gardens - but here writ in large scale. There were occasional fir or spruce trees breaking the skyline and what appeared to be rhododendron bushes. The sky was clear and the air was sharp - and I was losing my stamina.Just after 3pm I stopped when I encountered a handful of Bai people cutting wood and bamboo alongside the track. This made me lose heart. After all my hard work I still hadn't even ascended to a height beyond where the local people spent their ordinary working day. I sat down to have a drink and eat some of the greasy pancake-ish thing I’d bought for my lunch. Then with a heavy heart, I turned around and started on the great knee-jarring return trip back down into Dali. It was dispiriting because the age it took me to get down to the Zhonghesi temple made me realise how much upward effort I had put in for nothing. When I finally arrived back at the temple it was deserted, except for an old lady and a cockerel that attacked me from behind. So it was nice to eventually get back into Jim's Café, for a well-earned beer.

When I told Jim where I'd been, he smiled his hippy smile and said I should have told him what I was doing. Jim said he could have arranged a van to take me half way up the mountain, because there was a service road for the TV station that went almost as high as I had hiked that day. Despite my tiredness, I decided to take his advice and have another crack at the mountain after having a rest day.

And so, undaunted by the failure of my first attempt to knock off the peaks of the Cangshan mountains, I succeeded on my second attempt by cheating and getting a lift half way. I made sure I was better prepared this time, spending most of the intervening day lazing around outside Jim's Peace Café, soaking up the sun and partaking of beer, chips and whatever other western indulgences I fancied. Hanging out at Jim’s, I managed to recruit a few other backpackers - some Brits, a Mexican guy, a Swede and two Germans - who also expressed interest in taking a trip up to the top of the mountains.

Leaving Jim to make the arrangements, we hired bikes and freewheeled down the lanes out of Dali to see Erhai Lake.

It was a lovely cool and clear day. Away from the town, the scenery around the lake was almost biblical - a couple of traditional sailing boats drifting around on the mirror-like surface of the lake, with the mountain backdrop . In the surrounding fields the Bai peasants laboured away at ploughing and planting crops by hand, while we decadent westerners sat around drinking Coke. The houses looked decrepit and the locals had spread rice and grain out on the road to dry it out.

Early the next morning we all assembled in the cold street outside Jim's café and he marshalled us past a young PLA soldier who was standing guard at the city gate, gripping an AK47 like he meant business. A tiny beat-up ‘van’ took us up a rough switchback dirt track, never getting out of second gear for the whole hour it took us to get to the end of the road. I was terrified by the sheer drops and wild exposure on each of the hairpin bends, but managed to control my panic until we reached the terminus, more than half way up the mountainside. We seemed to be at about the same level as I'd reached after my tough all day uphill slog two days before.

We had nice clear weather to begin with, but clouds soon built up around the peaks and threatened to envelope us. Soon we were climbing up through a swirling cold mist, along a well-cut track through the long brown grass. Suddenly, we emerged from the mist and found ourselves actually looking down on a carpet of white cloud. The summit still looked a long way off and the altitude started to kick in again, rendering me breathless after only a short period of exertion. My lungs felt as if they were going to burst and I thought my heart would rupture, and it took us more than two more hours to get within striking distance of the summit. We reached a grassy plateau, where the birds sang and the sun shone, and it felt like I was ascending into heaven.

We had nice clear weather to begin with, but clouds soon built up around the peaks and threatened to envelope us. Soon we were climbing up through a swirling cold mist, along a well-cut track through the long brown grass. Suddenly, we emerged from the mist and found ourselves actually looking down on a carpet of white cloud. The summit still looked a long way off and the altitude started to kick in again, rendering me breathless after only a short period of exertion. My lungs felt as if they were going to burst and I thought my heart would rupture, and it took us more than two more hours to get within striking distance of the summit. We reached a grassy plateau, where the birds sang and the sun shone, and it felt like I was ascending into heaven. The last thousand feet or so of ascent was relatively easy and before we knew it we had reached the "TV station" - a concrete blockhouse festooned with aerials and with a large TV satellite dish.

The last thousand feet or so of ascent was relatively easy and before we knew it we had reached the "TV station" - a concrete blockhouse festooned with aerials and with a large TV satellite dish.The wind was blowing hard so we plonked ourselves down on the leeward side of the building for shelter, to have lunch and a drink. A door opened and a Chinese workman in a blue Mao suit emerged, to gaze at us for a minute with a blank expression. It was as if it was nothing out of the ordinary for their remote station to have visitors, let alone foreign ones. Without saying a word the man emptied a bin of rubbish down the side of the mountain and went back inside. A few minutes later, another technician emerged bearing a thermos flask of hot water, from which we gratefully filled our mugs and bottles, and I was able to make a cup of Earl Grey from one of the few teabags I’d brought along.

The views were absolutely breathtaking on all sides, looking down on the pine forests that covered the ridgelines until they disappeared into the clouds. Dark razorback ridges of rock snaked menacingly towards the other peaks in the Cangshan range, and in the distance to the north, the snow peaks of the Jade Dragon mountain range near Lijiang were visible. And yet ironically, immediately below us, Dali was obscured by cloud. We posed for a few pictures, and then set off to return.

The views were absolutely breathtaking on all sides, looking down on the pine forests that covered the ridgelines until they disappeared into the clouds. Dark razorback ridges of rock snaked menacingly towards the other peaks in the Cangshan range, and in the distance to the north, the snow peaks of the Jade Dragon mountain range near Lijiang were visible. And yet ironically, immediately below us, Dali was obscured by cloud. We posed for a few pictures, and then set off to return.The Germans headed back down the way we had come up, while the rest of us decided to explore a little further along the ridge to the south, where there appeared to be a slightly higher peak about half a mile away. The path petered out and we soon found ourselves scrambling up a steep hillside covered in knee high scrub until we came out on to a narrow platform of rock that formed the summit. We were rewarded by spellbinding views down into a series of sheer gullies and gorges that dropped off to the west. I felt giddy and lacked the courage to even stand up on such an exposed spot. Instead, I sat and rebuilt a small stone cairn that previous visitors had piled up.

We reluctantly left the summit and headed down towards a small tarn on a plateau, where we rejoined a well-formed track. From there it was another knee-jarring descent, back down into the cold clouds and towards the tree line, where we crossed paths with a party of local workmen who were busy hacking away to widen the overgrown track. No sign of the missing two porters, they told us.

We reluctantly left the summit and headed down towards a small tarn on a plateau, where we rejoined a well-formed track. From there it was another knee-jarring descent, back down into the cold clouds and towards the tree line, where we crossed paths with a party of local workmen who were busy hacking away to widen the overgrown track. No sign of the missing two porters, they told us. From there it was a long and leg-torturing descent for more than an hour, over now familiar territory back down to the Zhonghesi temple. Here, we paused for a very refreshing cup of strong and bitter green tea before continuing on down, almost limping into Dali and a peak-conquering-victory drinking session at Jim's Peace Café.

From there it was a long and leg-torturing descent for more than an hour, over now familiar territory back down to the Zhonghesi temple. Here, we paused for a very refreshing cup of strong and bitter green tea before continuing on down, almost limping into Dali and a peak-conquering-victory drinking session at Jim's Peace Café.After the initial 'mission accomplished' euphoria, the rest of the evening was a dull anticlimax.

The rest of my brief China trip was also something of an anticlimax. This was partly because I was now back-tracking through the same places: Kunming, Guilin and Wuzhou, back towards Hong Kong, with the consequent feeling that my trip had past its ‘high tide’ mark and there were no more new places to discover. On later trips I was to find this was a common feeling - once my goals had been achieved I soon lost interest and enthusiasm for China, and just wanted to move on. And once I had mentally set my mind on being in the next place, my patience with the minor irritations of Chinese life quickly ran out. The things that had once seemed novel and funny in the first few days of travelling in China were now often just a reminder of what an alien environment I was in. I soon got tired of the what I came to call the “Six Annoying 'S's” of China: the spitting and staring, the shoving and shouting, the slurping of tea and the incessant smoking.

When my bus stopped on a stretch of rural road for a toilet break, the male Chinese male passengers would adopt a peasant squat by the roadside and eye me impassively as they puffed on their cigarettes. They dressed in cheap black and grey suits that still had a big label sewn onto the sleeve, as if fresh from a bespoke tailor. They would hoick up a throatful of phlegm and spit without taking their eyes off me - was this a calculated insult? I couldn't understand what they were saying to each other as they stared and snickered at me, except for the constantly recurring word laowai – ‘foreigner’.

When my bus stopped on a stretch of rural road for a toilet break, the male Chinese male passengers would adopt a peasant squat by the roadside and eye me impassively as they puffed on their cigarettes. They dressed in cheap black and grey suits that still had a big label sewn onto the sleeve, as if fresh from a bespoke tailor. They would hoick up a throatful of phlegm and spit without taking their eyes off me - was this a calculated insult? I couldn't understand what they were saying to each other as they stared and snickered at me, except for the constantly recurring word laowai – ‘foreigner’.Sometimes I felt like I was a character in Planet of the Apes - a weak human who had fallen into a strange post-apocalyptic world populated by beings who were both smarter than me and yet more callous and primitive. At other times the Chinese people I met were touchingly open and generous. Later, sat on the back of a long distance bus in Guangxi, I found myself wedged between a bunch of teenage kids who were already hardened manual workers judging by the dirt on their suits. Despite their rough appearance they prodded me into sharing their snacks of monkey nuts and mandarin oranges. They spoke no English and I spoke little Chinese, but I understood their gestures when they flicked through my paperback book and gawped at the English words and gave me the thumbs up sign. "Zhen hao!" ('Very good!')

I departed China via Hong Kong in November 1990. In this pre-internet era I had been cut off from the world while in rural China for three weeks. It was only when I arrived at the Tsim Sha Tsui ferry terminal in Hong Kong and bought a South China Morning Post that I learned that Margaret Thatcher was no longer the Prime Minister of Britain. I had missed the end of the Iron Lady while I was in the China news black hole.

Yunnan Postscript

From Hong Kong I flew to Perth in Australia and did the whole backpacker tour of the big continent. I travelled the long dusty red highway up through the Kimberley to Darwin and then down through the ‘red centre’ to see Alice Springs and Ayers Rock. But even though I saw some amazing sights, I felt unsettled and unsatisfied with Australia. I didn't realise it then, but I had caught the 'China bug'. Already I yearned to see more of China, this country that was just so ‘other’ compared to the west. I also missed the feeling of adventure that came with being on the road in China. In Australia I was no longer the centre of attention, no longer the big tall guy in a crowd. In fact, compared to the big bronzed Aussie blokes I was now the weedy pale European guy.

Soon afterwards I moved on to New Zealand, where I found a job as a journalist and settled down in Auckland for a while, indulging my love of the outdoors with a lot of tramping and mountaineering in the rugged New Zealand bush. I was to spend the next four years in New Zealand, and during this time I married a girl from China (that's another story) and started to study Chinese. It was in Auckland, of course, that I also first stumbled across the articles by Joseph Rock about south-western China. I nurtured a growing curiosity about the places he described. It was not until 1994, however, that I returned to China to try see them for myself.

Soon afterwards I moved on to New Zealand, where I found a job as a journalist and settled down in Auckland for a while, indulging my love of the outdoors with a lot of tramping and mountaineering in the rugged New Zealand bush. I was to spend the next four years in New Zealand, and during this time I married a girl from China (that's another story) and started to study Chinese. It was in Auckland, of course, that I also first stumbled across the articles by Joseph Rock about south-western China. I nurtured a growing curiosity about the places he described. It was not until 1994, however, that I returned to China to try see them for myself.

2 comments:

what a great read, am really impressed. thanks so much.

I've recently discovered your blog and it is lovely! Makes me want to go for a hike.

Post a Comment